In February 1929, Evelyn Waugh and Freya Stark documented their flight experiences, documenting their journey from London to Paris. Within the extracts, both writers have a tendency to firstly, explain the reasons for their travel and secondly, to describe their flight experience as a whole. Their narratives contain a lot of flamboyant and perhaps, exaggerated, terminology which is likely due to their feelings of excitement, exhilaration and nervousness. Waugh in particular, in the longer extract of the two, describes the whole journey; describing his belongings, itinerary for the trip, the process of check in and the flight experience itself. Waugh’s journey reflects several transport tourist theories from this decade, as ‘the air service was still very young’ (Waugh, 1982, p.187) therefore, Waugh’s descriptions support the common idea that it was not until ‘the second half of the twentieth century that jet propulsion, wide-bodied aircraft and low-cost carriers helped to create and accelerate mass tourism’, Pirie states in his article that 1920’s air travel was not available for the masses due to its expense and most flights would have carried government officials (Pirie, 2009, p.49). Other travel tourist theories which will be discussed in relation to Waugh’s extracts will be: early desires to fly, the potential beginnings of ‘tourism’, technological advancements and commercialisation of air travel.

Brave Socialites and Uncomfortable Beginnings

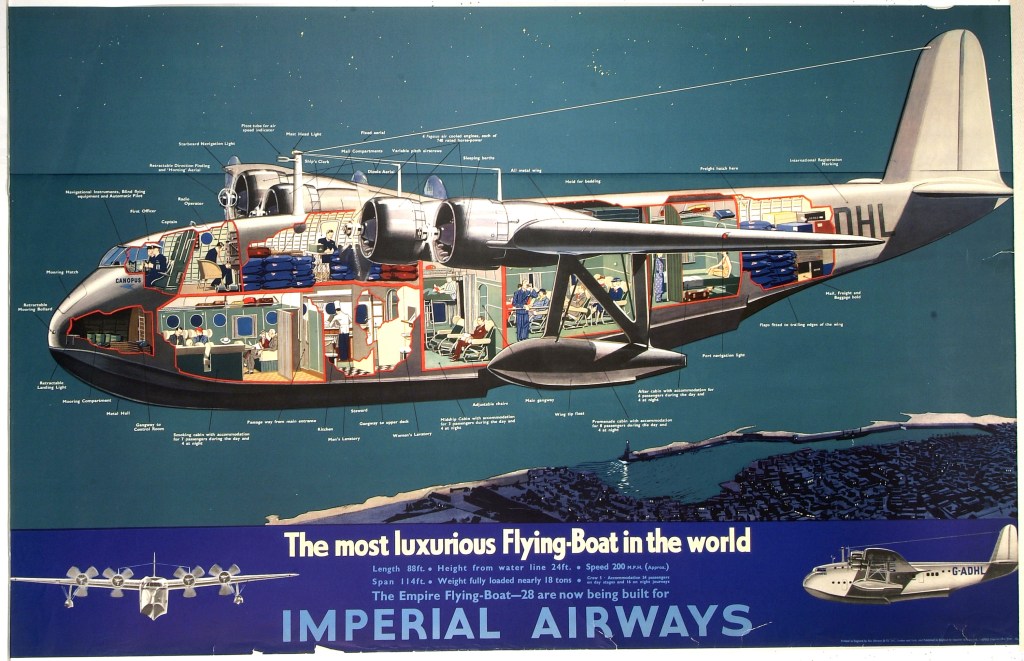

Immediately after World War One, an important decision was made by the British government which essentially kept aviation alive. Planes were not advanced enough at this point to fly in winter months and therefore, as Peter Lyth states: where profits soared throughout the summer, aviation was practically non-existent at the end of the year: ‘summer boom was inevitably followed by a winter slump’ (Lyth, 2000, p.868). Imperial Airways, a government-sponsored company, advanced the air travel industry from 1923.

Evelyn Waugh’s extract gives a fine example of a product within a growing industry, still under a trial and error process; Waugh uses his descriptions to imply how people would try anything to get the chance to fly: ‘an ex-officer of the R.A.F. appeared in Port Meadow with a very dissolute-looking Avro biplane, and advertised passenger flights for seven and sixpence or fifteen shillings for “stunting”’ this suggests how people were willing to pay small fortunes, to fly in very inadequate post-war aircrafts (Stark & Waugh, 1982, p.188). Despite these stunt flights not particularly advancing ‘mass tourism’ as such, people in the 1920s were desperate for a taste of flying, and it was only the matter of expense of a real destination flight which stopped people from doing so.

In the context of Waugh’s writings, 1929, this was a period of quality advancement for aviation. It saw the beginnings of ‘first-class’ on-board service: The Silver Wing (BBC 4, 2009). This was a period of fortune for those who were affluent, despite the Great Depression, wealthy personnel would pay fortunes to experience the recent advancements in aviation in terms of silver-spoon styled service. The BBC documentary on post-war aviation goes into detail about this growing craze, suggesting it was a government idea to advertise British aviation with the idea of promoting their ‘modernity and technological prowess’ (BBC 4, 2009). Unfortunately, in terms of tourism for the masses, this craze was mainly used by diplomats and government officials; this knowledge is backed up by Gordon Pirie who suggests: ‘the main reason for the relatively small share of leisure air travel by air in the British Empire is probably the expense of tickets’ (Pirie, 2009, p.54). However, as in Waugh’s extract, there were less expensive options of flying: ‘it was not the newest sort because they are more expensive’ this is one of the early beginnings in mass travel and tourism; as technologies advanced, the more recent planes were left behind by the growing companies therefore, more of the masses could begin to experience flight, despite being years behind the wealthy customers (Stark & Waugh, 1982, p.191).

Reasons for Flying and Taking Risks

Evelyn Waugh, more so than Freya Stark obtains the general feeling of excitement for flight through his use of adjectives throughout the extract: ‘excited’ ‘trembling’ ‘fascinating’ ‘clean and bright’, this supports the perception of the masses at this time, Waugh’s experience is one of highs and lows, literally and mentally, he experiences moments of relaxation as they seemed to ‘float along’ opposed by feelings of ‘discomfort’ as he was sick and experienced a ‘headache’ due to testing nature of the flight (Stark & Waugh, 1982, pp.188-192). This mixture of feelings is what Pirie describes as he suggests ‘flying was not just about the balancing of savings and cost, it was about the conspicuous consumption, boasting and thrill’ despite the disastrous end to Waugh’s flight and Stark’s feeling of being ‘dishevelled’, people paid for the experience to boast and tell their friends, which was also a fast way of spreading the desire to fly (Pirie, 2009, p.55) (Stark & Waugh, 1982, p.187). In the next section, the intelligence of companies to take advantage of people’s wish to fly was part of their advertisement, alongside the travelogues of those who sought tourism for the first time.

What came first, the chicken or the egg?

A long-debated question about the symbiotic relationship between transport and tourism is which came first? Did the development of transport lead to a demand for tourism, or did a demand for tourism lead to pioneers creating better transport industries? In terms of the creation of aviation, the small demand pre 1914 was much more insignificant than post World War One, when a thirst for demand came as a result of ‘astonishing technological implications’ through combat (Zuelow, 2015, p.127).

As time progressed, so did aviation. In Waugh’s documentations, he includes the use of Imperial Airways advertisements, one of many posters which captured the imagination of the country (Stark and Waugh, 1982, p.190). Advertisements showing proud-looking, well-dressed businesswomen as the ideal model for flights demonstrated the feelings of aviation at this time. An interpretation drawn from posters such as the one shown in the extract, is that business women who chose to afford the ‘less expensive’ journeys, alike the woman on the flight with Waugh, would see these advertisements and potentially model herself on the affluent business traveller. Therefore, the cheaper and shorter flights could be used by common people like Stark and Waugh who are seeking the beginnings of their tourist life.

British Airways: Photographs from 1920-1929.

Furthermore, in Pirie’s article, he states that despite a complete advancement in long-distance flights, the stopping and starting nature of reaching a far destination was one of the early causes of enlightened tourism: ‘frequent stopping, and overnight halts, helped to make tourists of all air travellers, irrespective of their trip purpose’ as well as this, it is noted that whilst the travellers were on the ground, they would begin to document the places they saw and visited which became early versions of travelogues which would be circulated throughout the country, installing a mass tourist agenda (Pirie, 2009, p.56). From Waugh’s extract, you can gather the sense that he is not particularly driven on the notion of sight-seeing, ‘it was sensible on the stomach rather than the eye’ his focus on the discomforts would have been a common thought for first time passengers who would not have been able to compose themselves to focus on sightseeing (Stark & Waugh, 1982, p.191).

Conclusion

When analysing Waugh’s experience, it is important to see his extract as a whole journey. The sense of preparation, check in, meeting new people, excitement, fear and destination are all themes of what became of the travel holiday. Despite Waugh’s lack of desire for sightseeing or his disinterest in the destination, his accidental participation, in the simplest way of him documenting his experience became the makings of travelogues and spread the mass demand for travel. As aircrafts became steadier, safer and more relaxed air travellers became tourists even in the sense of them viewing the ground below. Pirie states that ‘air tourism was a product of the age before society had been saturated with aerial photography’ which is a perfect representation of the correlation between technological development and mass tourism (Pirie, 2009, p.64). As previously mentioned, the complete acceleration of mass travel did not occur until post World War Two when there was further technological developments which led to cheaper manufacturing of planes, and tourists could travel for destination at affordable prices.

Bibliography:

BBC 4 (2009) High Flyers: How Britain took to the Air. A documentary celebrating the golden age of air travel during the 1920s and 1930s. London: BBC. (DVD).

Lyth, P. (2000) ‘The Empire’s Airway: British Civil Aviation from 1919-1939’. Revue belge de philogie et d’histoire. 78 (3-4), pp.865-887.

Pirie, G. (2009) ‘Incidental Tourism: British Imperial Air Travel in the 1930s.’ Journal of Tourism History 1(1), pp.49-66.

Stark, F. & Waugh, E. (1982) ‘A Trip to Paris.’ In Kennedy, L (ed.) A Book of Air Journeys. London: Collins, pp.187-193.

Zuelow, E. (2015) ‘Bicycles, Automobiles and Aircraft’. In, A History of Modern Tourism. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp.112-133.