___________________________________________________________________________________________

Dark tourism has been tickling the taste (or more so travel) buds of Brits for hundreds of years. It is easy to assume that dark tourism is a new commodity and is only associated with those who wish to thrill-seek or have a passion for the macabre. However… whenever, and wherever death occurs, curious people tend to follow. This even dates back to 500AD whereby “the first identifiable phase of dark tourism in numbers was Christian Pilgrimage” (Seaton, 2018 p28) so dark tourism has basically been around forever!

There are many variables surrounding dark tourism so the chances are that you yourself can be classed as a dark tourist due to the complex definitions surrounding it. For those who may not understand nor have a fascination with death, dark tourism can subconsciously “invite us to recognise the fragility of life in general, as well as our individual mortality and relative insignificance in the universe” (Bowman et al, p189), making the very idea of dark tourism somewhat valuable to the human experience.

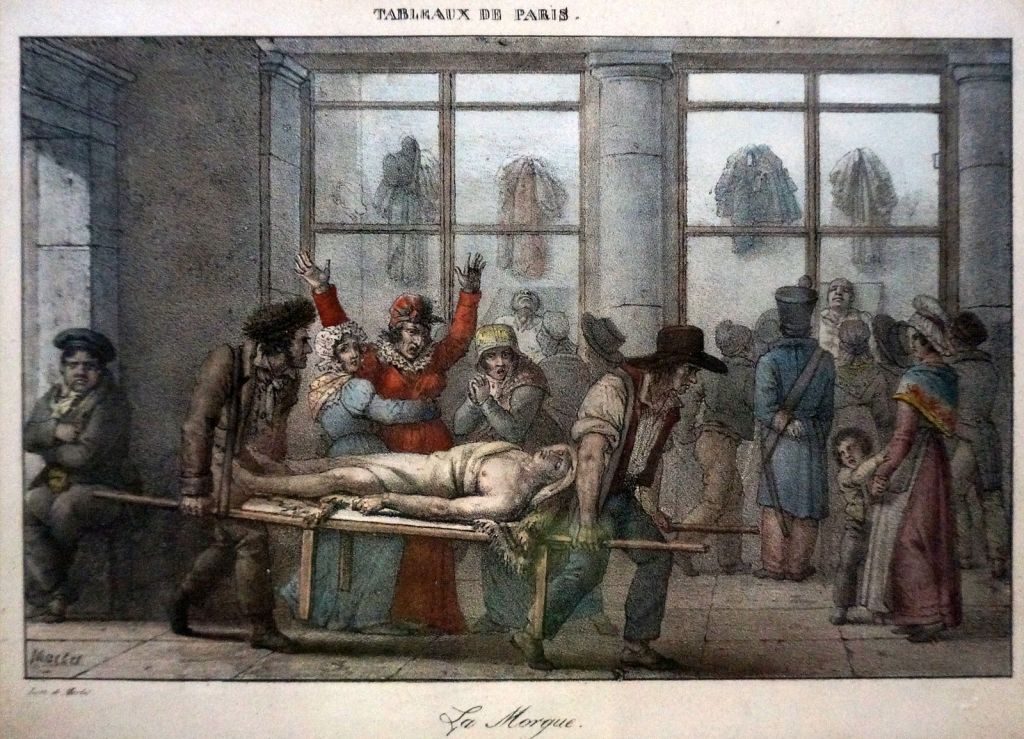

Fig 1 – Image of the Paris Morgue, a popular tourist destination in the 1800s. – Marlet, J. (before 1847). Morgue de Paris. Uploaded by: Garitan, G. (2014). Available: Wikimedia Commons.

What can be classed as dark tourism?

_____________________________________________

According to Seaton (2009), a key researcher within dark tourist attractions, there are five key typologies; public enactment of death (this relates more to executions further back in history), mass death sites such as battle fields, war memorials, symbolic representations (like what you may see in a museum), and re-enactment. Many different ‘destinations’ or ‘sites’ can be put into these typologies, making them quite hard to define. Even though the dark tourist may not be consciously aware, nor thrill-seeking, it is still and has been an attractive reason for Brits to travel. People crave experience and visiting a dark tourist site allows them to empathise and be present in the history of the place. Furthermore, people may travel with the sense of collective identity, to honour those departed. Examples of this may include the National September 11 Memorial Museum and Auschwitz.

An early definition of dark tourism, curated by Seaton draws on dark tourism being to “travel to a location wholly, or partly motivated by the desire for actual or symbolic encounters with death” (Seaton, 1996 p240). However, he now describes that these places are engineered and orchestrated to remember mortality and fatality. Even though people visit these places may go out of symbolic reason or respectfulness, the place in question has been created to do so with reason and with commercialisation.

Within western historiographical terms, reasons for the visitation of such places can be due to ritualisation, antiquarianism and more aesthetically, romanticism. People like to romanticise what once was, leading to the fascination towards places that once were. There is also the potent value of viewing or learning about specific history up close, to make sure it doesn’t happen again.

There are many first-hand historical and modern accounts which describe different types of dark tourism for different reasons, yet each account holds the stark similarity of being both effected by their trip and showing the evident orchestration of places of death and or destruction:

The Past and the Present –

What were people’s experiences as dark tourists?

_____________________________________________

The Battle Site of Waterloo:

Robert Southey visited the battle site of Waterloo the Autumn after its occurrence in 1815. In his recount he mainly speaks of the capitalisation of the battlefield, and the evident contrast compared to the realities of the battle, and what they were doing on the tour. He stated that they had “bread and cheese, wine and fruit” (Southey, 1816) in the same place where the “bone of one leg with the shoe on is lying above ground” (Southey, 1816) which shows the orchestration of this tour.

Even though this recount is from 1815, there are still elements of modern-day tourism, consolidating the idea that dark tourism and the engineering of it as a commodity has always and will always be around. Robert states that he purchased “a French pistol and two ornaments of the French infantry cap for six francs” (Southey, 1816) almost as if he were in a gift shop. This, along with dining on top of a potential burial site shows that the tour was planned as a form of leisure, and those selling items, and the tour itself could capitalise on the tragic battle.

Fig 3 – Film poster for a re-enactment of the Battle of Waterloo. By Daily Alaska Dispatch Newspaper. (1914). Battle of Waterloo 1914. Uploaded by: JKBrooks85. (2014). Available: Wikimedia Commons.

In Contrast to Robert Southey, Charlotte Eaton visited the battle ground in June 1815. She notes that “melancholy were the vestiges of death that continually met our eyes. The carnage here had indeed been dreadful” (Eaton, 1817) which shows the tour, and her surroundings had an extremely negative and profound effect on her. She further describes in detail the gruesome remains of horses and the evident death and destruction of which occurred at this site. Visiting this site as a tourist so soon after the atrocities, plays into the idea of morbid curiosity, and the need to be ‘self-involved’ in an event. Charlotte saw “piles of human ashes that were heaped up, some of which were still smoking” (Eaton, 1817) which to many would indicate that they were visiting too soon after the event. When travelling to dark tourist sites it is important to show respect and viewing fresh human ashes just because they wanted to visit can definitely be seen as disrespectful.

Chernobyl Exclusion Zone:

The Chernobyl disaster of 1986 left the city of Pripyat as a ghost town, due to the evacuation of people because of nuclear fallout. As time has progressed, the city has become to exemplify “darker aspects of scientific advancement and human experience and its ability to lure increasing number of tourists” (Yankovska, 2014 p935) as a dark attraction site.

Even though there is a lure for tourism, it is important to keep in mind and be respectful of the people who still reside at this dark tourist destination. In the case of Chernobyl, people who avoided the evacuation protocols still live in the exclusion zone and “rely on food from their gardens and the surrounding forest, including large and abundant mushrooms” (Kingsley, 2021) to survive. They also live around extremely high levels of radiation which is extremely health damaging. For someone to travel there as a dark tourist, whether their main goal is to thrill-seek or educate themselves, it can be seen as encroaching on these people’s lives, and almost romanticising what is in fact a very dangerous situation for those that decided to stay.

Fig 4 – Tourists visiting the Exclusion Zone. By Gilliland, C. (2014). Pripyat. Available: Wikimedia Commons.

In 2019, travel blogger Stephanie Hollman shared her experience of visiting the Chernobyl exclusion zone. She stayed there for a number of days and was given tours round the abandoned hospitals and saw “remnants of daily life” (Hollman, 2019) that were damaged by the disaster. Just like the Waterloo accounts from 1815, there were both examples of engineered tourism, and profoundly negative ‘thrilling’ emotions present on the trip.

For the first part she describes not feeling much emotion, until the stark realities of human life came to fruition. Entering Pripyat, where the disaster occurred, she found it “surreal to stalk around an abandoned city of a former 50,000 inhabitants and not see another soul (Hollman, 2019) which shows she felt profound emotions, as well as just wanting to ‘thrill-seek’.

“Whenever we saw a personal artefact, I started to feel those sickening twinges of reality sinking in a single shoe, a coat on a doorknob, a framed photo on the windowsill, or a carton of milk still sitting on the kitchen table.”

stephanie Hollman, 2019

The feelings she experienced whilst exploring are indicative to the general experience of the dark traveller, whether intending to thrill-seek or not. It is common to be faced with artefacts of loss and death as “feel a sense of anxiety and vulnerability about death in ways that can challenge senses of self” (Light, 2017 p289) as seeing this made her re-evaluate her lack of feelings on the trip.

“We ate traditional Ukrainian meals at Chernobyl’s only restaurant and stocked up on snacks (and vodka) at its only convenience store. Our humble hotel provided hot showers and we even had access to reasonably fast WIFI. We also learned of a fully functioning post office, basic health clinic, and fully stocked bar that served to entertain its residents.”

Stephanie hollman, 2019

This extract from her blog post demonstrated the idea of the tour being engineered with guests in mind, rather than the place being cut off and labelled only as a place of history. Having amenities such as WIFI and being able to have traditional food and drink (Just like Robert Southey in Waterloo) commoditises the disaster site, turning it into a strictly tourist space.

Check out her full blog post here

_____________________________________________

As suggested within these different accounts of dark tourism, the main aspect, aside from the commodification of the sights is the “remembrance of the death and the dead, induced by symbolic representations” (Seaton, 2018 p24) and that some people visit these places to feel like they are part of the history. However, the idea of being a ‘dark’ tourist does not always mean to be gruesome and negative. It is important that “dark places cannot be considered solely as vehicles of reflection on death” (Buda et al, 2020 p681) more so a place of history and great importance to remember that the people involved once lived, and often came to a horrific end.

Bibliography

_____________________________________________

Bowman, M AND Pezzullo, P. (2010). What’s so ‘Dark’ about ‘Dark Tourism’?: Death, Tours, and Performance. Tourist Studies. 9 (3), 187-202.

Buda, M D. AND Martini, A. (2020). Dark tourism and affect framing places of death and disaster. Current Issues in Tourism. 23 (6), 679–692.

Eaton, S (1817: 1888) Waterloo Days: The Narrative of an Englishwoman Resident at Brussels in June 1815. London: George Bell & Sons.

Hollman, S. (2019). My Experience Visiting the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone. Available: https://travanietravels.com/chernobyl-reflections/.

Kingsley, J. (2021). Life goes on at Chernobyl 35 years after the world’s worst nuclear accident. Available: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/life-goes-on-chernobyl-35-years-after-worlds-worst-nuclear-accident.

Light, D. (2017). Progress in dark tourism and thanatourism research: An uneasy relationship with heritage tourism. Tourism Management. 61 (1), 275-301.

Seaton, T. (2018). Encountering Engineered and Orchestrated Remembrance: A Situational Model of Dark Tourism and Its History. In: Stone, R P The Palgrave handbook of dark tourism studies. London: Palgrave Macmillan. 22-33.

Seaton, A. V. (1996). Guided by the dark: From thanatopsis to thanatourism. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 2(4), 234–244.

Robert Southey (1816: 1903) A Journal of a Tour of the Netherlands in the Autumn of 1815. London: Heinemann

Yankovska, G. AND Hannam, K. (2014). Dark and Toxic Tourism in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone. Current Issues in Tourism. 10 (17), 929-939.