Dark Tourism: War and the Maltese Archipelago

“Death is the one heritage that everyone shares. It has been an element of tourism longer than any other form of heritage.”

(Seaton, 1996).

Strange Bedfellows

Theoretical frameworks describe dark tourism as travel to sites related to tragedy, death, or suffering, such as natural disasters, genocides, or conflict zones (Seaton, 2009; Cohen 2018), and, although scholarly interest in the topic is relatively recent, the practice is certainly not. While it’s not always easy to see how violence and atrocity might be connected to pleasurable holidays, its growth in popularity and potential to generate income suggest that dark tourism, more latterly described as ‘orchestrated remembrance’ (Seaton, 2018), has a bright future as part of an evolving travel landscape.

Considered a significant agent in the creation of modern mass travel, the Second World War itself provides a rich vein of dark tourist sites, its concentration camps, battlefields, and artefacts remaining popular amongst those with an interest in death, suffering, and destruction (Kasimoglu, 2012; Butcher, 2020).

Malta, a Mediterranean archipelago with a long and turbulent history, is filled with reminders of a past scarred by conflict, and its wealth of wartime sites provide a heady mix of tragedy, history, and heroism, where echoes of the war can be felt. Importantly, rather than mere reconstructions or re-imaginings of dark events, its locations are all genuine ‘primary’ sites (Robb, 2009), created “within the memories of those still alive to validate them”, enjoying an air of authenticity (Lennon and Foley, 2000, p.485). Recognising the uniqueness of its legacy, Heritage Malta, the body responsible for the preservation of all historical sites, has begun to exploit their economic potential. In promoting Malta as an important ‘conflict’ tourist destination (Tunbridge, 2009), it appears that war and tourism might not be such strange bedfellows after all.

A Crossroads of Conflict

Playing pivotal roles in struggles across the centuries, Malta has always been central to the historical interplay between Europe, Africa, and the Middle East. Part of the British empire since 1814, it gained independence in 1964, and was declared a republic ten years later.

73,156 sorties flown against Malta between 1940-43.

1,581 civilians killed as a result of enemy action.

7,500 servicemen and merchant seamen killed.

3,780 people injured.

15,000 tonnes of bombs dropped, 4 times more than Dresden

30,000 buildings destroyed or damaged.

50,000 people made homeless.

7,433 unexploded bombs dealt with by the Royal Engineers.

Wartime Statistics. Source: The Malta Independent.

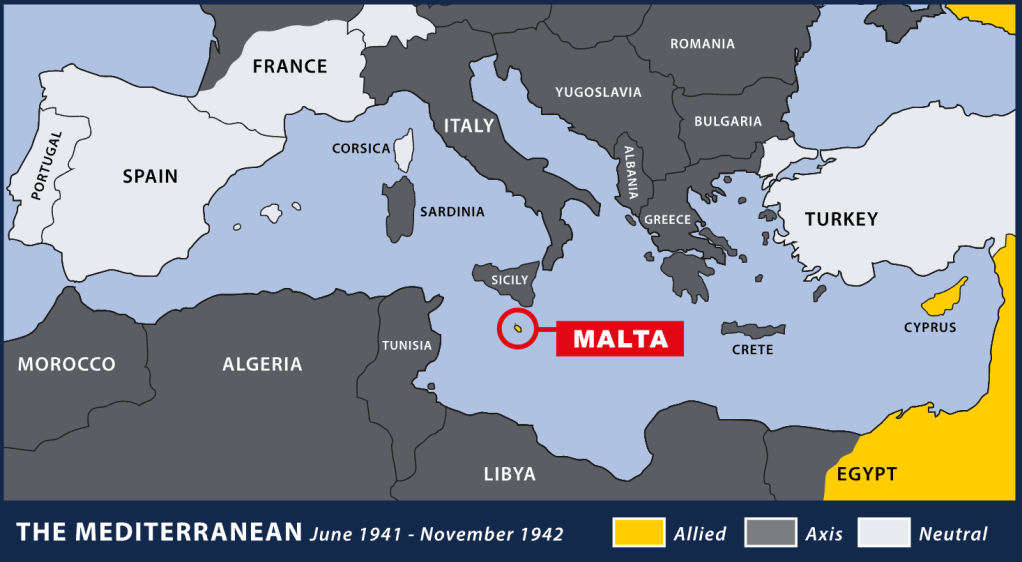

During the war, its position at the heart of the Mediterranean meant Malta had critical strategic importance for both sides. Had the Axis powers succeeded in overpowering the islands, they would have taken control of the North African theatre, including access to the Suez Canal, and the outcome of the war might have been different. Recognising its importance, the Italians and Germans bombed Malta relentlessly, launching 3,343 separate raids, in what become known as ‘The Siege of Malta’, granting it the unenviable record as the most bombed place on Earth during the war.

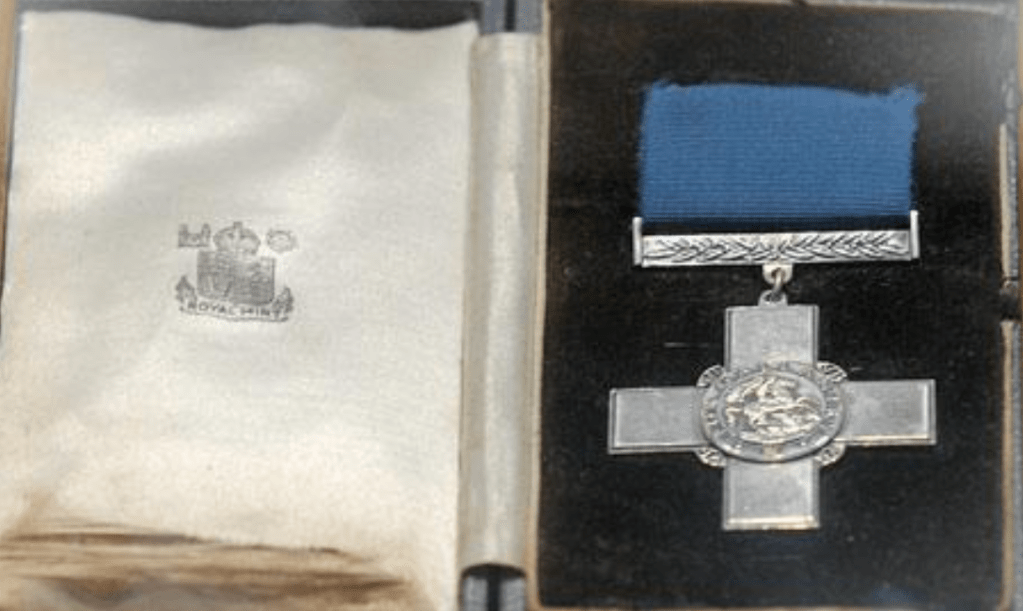

The George Cross, established by George VI in 1940, “for acts of the greatest heroism”, is the civilian equivalent of the Victoria Cross. Awarded to the islands in 1943 recognising the suffering and resilience of their people, Malta remains the only country to hold this honour, incorporating it into the national flag.

Source: Times of Malta

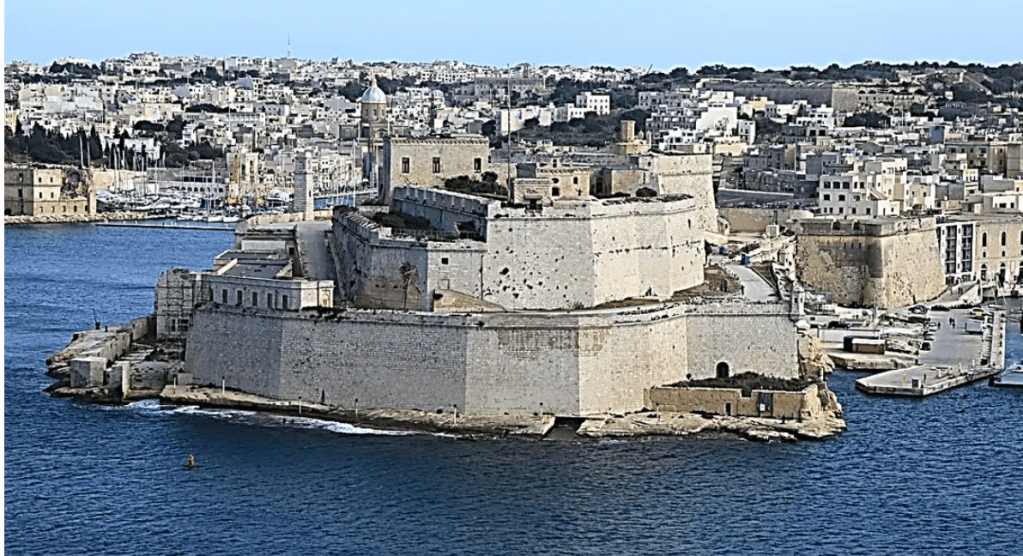

With cemeteries dotting the islands, bomb shelters at Mellieħa, Mġarr, and Ċirkewwa, the Lascaris War Rooms, St. Elmo’s naval fortress, and an unexploded German bomb (albeit a replica) sitting in a Mosta church, remnants of the war form a central plank of Malta’s tourist offering which welcomes over 2.3 million visitors every year, many anxious to explore the darker side of history.

Darkness, Death, and Dearly Departed

The motives driving those interested in visiting war graves, or examining instruments of death are as varied and nuanced as the histories revealed, ranging from acts of solemn remembrance to unashamed voyeurism. Lennon and Foley (1996, p.195) identify primary motivators as some combination of remembrance, education, and entertainment, while Bigley et al. (2010), offer a binary typology comprising intrinsic or extrinsic motivators, the former involving the visitor taking a personal interest in the site, using it as a vehicle for identification, commemoration, or grieving, while the latter being pedagogical in nature, involving a fascination with the macabre, an interest in modern warfare, or its destructive effect on society. However, Seaton (2018, p.13-27) contests that these dark encounters are symbolic, concerned with the remembrance of death and the dead, rather than with death itself, suggesting that research is unable to locate any group of tourists which accepts that death is its prime motivation.

Source: Visit Malta

Source: The Cultural Experience

Source: 123RF Images.

Source: Visit Malta

Source: Air Malta

Britons abroad certainly visit sites like the Pieta cemetery, Fort St Elmo, or Fort St Angelo for various reasons, many to establish or maintain familial ties with those who served, or are buried on the islands. The currency of these locations imbues them with an extra level of importance, enabling visitors to pay their respects in person in what is often a deeply emotional activity. Whether personally connected or not, graveyards in particular can also act as mediating spaces, bridging the gap between the living and the dead, allowing visitors to contemplate life, mortality, and death. However, neither of these performative, intrinsically-motivated encounters are driven by the ‘darkness’ of the location, but rather by deep emotional ties which transcend any classification (Sharpley and Stone, 2009).

“A privilege to visit my

Source: Lifenek

great uncle’s grave.”

The sites also present important pedagogical opportunities, because while there is a temptation to objectify, the tacit expectation nonetheless exists that by visiting challenging locations, visitors might reflect on how history guides the future, achieve a greater appreciation of suffering, or create a desire for lasting peace.

Though the experience of dark sites are neither uniform or objective (Robb, 2009), it’s important to differentiate between the ‘premeditated’ dark tourist who seeks out the macabre for entertainment or gratification, from the ‘accidental’ visitor who has personal links to locations classified as ‘dark’ (Bowman and Pezzullo, 2010).

“Travellers have different reasons for being interested in such sites: for some it’s catharsis, the search for answers, for others it’s about facing a heritage that hurts, and for others it’s mere curiosity.”

(Chetkuti, 2015).

Nevertheless, when memorials, tombs, and graveyards also become visitor attractions, grieving and entertainment are forced to take place at the same time, in the same space, blurring the line separating public and private, and creating an uneasy juxtaposition. It is the contradiction surrounding usage and intent which makes the narratives, and the manner in which they are presented, so challenging if antagonism is to be avoided. Fundamental to any curatorial decision-making is whether a moral equivalence is granted to all visitors irrespective of motivation, a dilemma compounded by the reality of modern commercial pressures.

Europe, Empire, and Britons Abroad

For Britons abroad, who account for almost a third of all visitors, the highest of any nation by far, the islands hold a special significance, their national pasts being inextricably linked. With echoes of empire and triumph against adversity, Malta’s wartime heritage allows these ‘modern antiquarians’ to bring idealised stories with them, connecting the suffering and ultimate triumph of both. Yet as Cassia (1999) warns, while an expected narrative of Allied heroism against a backdrop of Axis oppression might appeal to some, it tells only part of the story. Malta’s cemeteries, war rooms, and material artefacts therefore raise issues as to what exactly is being remembered and for whom. The dark sites have become places for the creation and consumption not only of Malta’s wartime memory, but of Britain’s, Italy’s, and Germany’s too. Yet in emphasising violence and brutality for the titillation of the visitor, the narratives presented risk misrepresenting, manipulating, or invalidating certain pasts, particularly those of non-Britons.

“I like to pay my

respectsto the brave

people who fought

for my freedom”

Source: Lathlane

The Saluting Battery, Valetta. Source: Visit Malta

Surprisingly, while the suffering of the Maltese is well chronicled, it is often used to create a backdrop against which British heroism can shine. In addition, dissonant heritages for German and Italian visitors have been created, portrayed universally as simply ‘the enemy’, in a strict victim-perpetrator binary. For Rui and Hung (2022), this requires negotiations which, given the economic importance of visitors from both of these nations, are now underway between the Maltese state, for Seaton (2018, p.14) the most important agent in creating more nuanced engineered remembrances, curators, acting as ‘memory makers’, and visitors as ‘memory consumers’ (Kansteiner, 2002).

“We went for remembrance and felt it was appropriate to come here [as] it is such a significant part of history. It was quite emotional.”

Source: Lydia C.

More prosaically, because Heritage Malta must pay for the upkeep of its wartime sites, as the older generations with personal links to the war die off, it is able to gradually deemphasise narratives tied to national identity, focusing instead on commemoration, shared suffering, and collective responses to conflict, narratives better aligned with European unity.

Relax, Respect, and Remember

Though an increasingly popular and important part of Malta’s tourist landscape, the presentation of its conflict sites remains controversial. While some consider their commercialisation a particularly crass and cynical form of entertainment, lacking the dignity and reverence demanded by such delicate subject matter, others see opportunities to learn, share, and face the horrors of collective pasts.

“What is crucial is that when people visit these places, there is great respect to the site.

(Chetkuti, 2015).

Dark tourism has to be ethical.”

Dark sites require an active collaboration between curator and consumer, both of whom have certain obligations to meet. Careful thought must be given not only to how Malta’s role in the Second World War is narrated, but how the many material artefacts which remain are presented to maintain historical fidelity while creating a viable dark tourist experience (Cochrane, 2015), what Seaton (2018, p.17) calls the ‘engineering and orchestration of remembrance’. The visitor, in their consumption and interpretation of what is on offer, must in turn remain respectful, aware of the weight of responsibility placed upon them as a transitory visitor passing through spaces commemorating the suffering of others.

A Bright Future for Dark Tourism

Conflict tourism can certainly be educational, cathartic, and deeply moving, a means of ensuring that victims are never forgotten, while the events are never repeated. The best sites clearly explain their past and the poignancy of the events that took place. Done sensitively and coherently, the impact on the visitor can be significant and lasting. However, done badly, conflicts can either be presented as sanitised, anodyne commodities, or descend into dramatized, exploitative voyeurism. A fine line must therefore be trodden between historical accuracy, solemn remembrance, and economic reality.

A recent study of European travel habits showed that destinations with a cultural heritage related to dark events are becoming increasingly popular (Juranović et al, 2021), and with a current worldwide value of almost £24 Billion, predicted to grow to nearly £29 Billion by 2032, dark tourism has a bright future. Malta’s centrality in a continent ravaged by war gifted it a unique legacy. If it is to take advantage of current trends, it must now re-engineer and re-balance its dark offerings to reflect a changed 21st Century audience.

Bibliography

Primary Sources – Images

123EF Images (2024) Unexploded bomb from the Second World War on the Church of the Assumption of Our Lady at Mosta. [Online Image]. Available from: https://www.123rf.com/photo_96171156_unexploded-bomb-from-the-second-world-war-on-the-church-of-the-assumption-of-our-lady-at-mosta-malta.html [Accessed 16 February 2024].

Air Malta (2023) Fort Rinella’s 100-ton gun. [Online]. Available from: <https://airmalta.com/en/blog/malta/fort-rinella> Available from: <https://www.cwgc.org/visit-us/visit-malta/> [Accessed 16 February 2024].

Commonwealth War Graves Commission (2024) Map of the Mediterranean 1941. [Online Image]. Available from: <https://www.cwgc.org/visit-us/visit-malta/> [Accessed 6 February 2024].

Commonwealth War Graves Commission (2024) War Memorial, Valetta. [Online Image]. Available from: <https://www.cwgc.org/find-records/> [Accessed 6 February 2024].

The Cultural Experience (2024) Grand Harbour Malta. [Online Image]. Available from: <https://www.theculturalexperience.com/tours/fortress-malta-battlefield-tour/> [Accessed 6 February 2024].

Times of Malta (2012) Malta’s George Cross. [Online Image] Available from: <https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/the-true-story-of-malta-and-the-george-cross.415417> [Accessed 18 February 2024].

Times of Malta (2019) Behind the closed doors of Fort St Angelo. [Online Image] Available from: <https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/behind-the-closed-doors-of-fort-st-angelo.711840> [Accessed 18 February 2024].

Visit Malta (2024) Firing the harbour battery. [Online Image]. Available from: <https://www.visitmalta.com/en/info/world-war-2-tourism-malta/> [Accessed 6 February 2024].

Visit Malta (2024) Lascaris war rooms. [Online Image]. Available from: https://www.visitmalta.com/en/attraction/lascaris-war-rooms-malta/ [Accessed 16 February 2024].

Primary Sources – Websites

Camilleri, M. (2020) ‘The World War Two siege of Malta in numbers.’ The Malta Independent. [Online]. 31 May 2020. Available from: <The Malta independent Archive> [Accessed 7 February 2024].

Chetcuti, K. (2015) ‘Dark side of tourism that fascinates holidaymakers.’ The Times Malta. [Online]. 10 February 2015. Available from: <The Times Malta Archive> [Accessed 7 February 2024].

Commonwealth War Graves Commission (2024) Discover Malta’s world war history. [Online]. Available from: <Commonwealth War Graves Commission> [Accessed 11 February 2024].

Future Marketing Insights (2024) Dark tourism market overview (2022 to 2032). [Online]. Available from: <https://www.futuremarketinsights.com/reports/dark-tourism-sector-overview> [Accessed 11 February 2024].

Reports and Insights (2024) Dark tourism market report. [Online]. Available from: https://www.reportsandinsights.com/report/dark-tourism-market [Accessed 18 February 2024].

Statista (2024) Number of international tourists in Malta from 2001 to 2022. [Online]. Available from: <https://www.statista.com/statistics/444781/number-of-overnight-inbound-visitors-to-malta/> [Accessed 7 February 2024].

Secondary Sources

Bigley, J. D. et al. (2010) ‘Motivations for war-related tourism: A case of DMZ visitors in Korea’. Tourism Geographies, 12(3), pp. 371-394.

Bowman, M. and Pezzullo, P. (2010) ‘What’s so dark about dark tourism?: Death, tours, and performance’. Tourist Studies. 9(3), pp. 187-202.

Butcher, J. (2020) ‘Constructing mass tourism’. International Journal of Cultural Studies. 23(6). pp.898-915.

Cassia, P. S. (1999) ‘Tradition, tourism and memory in Malta’. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 5(2), pp. 247–263.

Cochrane, F. (2015) ‘The paradox of conflict tourism: The commodification of war or conflict transformation in practice’? The Brown Journal of World Affairs, 22(1), pp. 51–69.

Cohen, E. (2018) ‘Thanatourism: A comparative approach’. In: The Palgrave handbook of dark tourism Studies. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 157–71.

Freiderich, M. (2018) ‘Dark tourism, difficult heritage, and memorialisation: A case study of the Rwandan genocide’. in: Stone, P. R. et al. (eds). The Palgrave handbook of dark tourism studies. London, United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 261-290.

Juranović, N. et al. (2021) ‘Dark tourism in the EU: Are we aware of taking part in It’? Open Journal for Research in Economics 4: pp. 19–30.

Kansteiner, W. (2002) ‘Finding meaning in memory: A methodological critique of collective memory studies’, History and Theory, 41(2), pp. 179–97.

Kasimoglu M (2012) Visions for global tourism industry: Creating and sustaining competitive strategies. InTech.

Lennon, J. and Foley, M. (2000) Dark Tourism: The attraction of death and disaster. Continuum, London and New York,

Robb, E. M. (2009) ‘Violence and recreation: Vacationing in the realm of dark tourism. Anthropology and Humanism, 34, pp.51-60.

Rui Su & Hyung Yu Park (2022) ‘Negotiating cultural trauma in tourism’. Current Issues in Tourism, [Online]. Available from: <Current Issues in Tourism Archive> [Accessed 11 February 2024].

Seaton, A. V. (1996) ‘Guided by the dark: From thanatopsis to thanatourism’, International Journal of Heritage Studies, 2(4), pp. 234-244.

Seaton, A. V. (2018) ‘Encountering engineered and orchestrated remembrance. A situation model of dark tourism and its history’. in: Stone, P. R. et al. (eds). The Palgrave handbook of dark tourism studies. London, United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan. pp.9–32.

Sharpley, R. and Stone, P. R. (2009) The darker side of travel: The theory and practice of dark tourism. Bristol, UK: Channel View Publications.

Stone, P. R. et al. (eds) (2018) The Palgrave handbook of dark tourism studies. London, United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan.

Tunbridge, J. E. (2009) ‘Forging a European heritage: The role of Malta’. Geographische Zeitschrift, 97(1), pp. 12–23.