‘The TB sufferer was a dropout, a wanderer in endless search of the healthy place. TB became a new reason for exile, for a life that was mainly travelling’.

(Sontag, 1978, p. 9)

Romantic descriptions of phthisis, or poet-killing disease, are imbued with a quasi-religious fervour and a frantic desire to sentimentalise what contemporaries now think of as a wholly unappealing disease. Victorian literature characterised the tubercular as a solitary sufferer, consumed with passion and feverishly scrambling to extend a fleeting existence. With this sentiment, the high altitude sanatoria was the most romantic place of respite. From the mid-nineteenth century, invalids flocked to the Alpine mountains to improve their physical and spiritual well-being in the radiant, crisp climate (Frank, 2012, p. 196).

‘Being a mountaineer came to be seen as an important qualification for undertaking the poetic role’ (Bainbridge, 2020, p. 162).

Airs, Waters and Places

‘Whoever wishes to investigate medicine properly, should proceed thus… [consider] the winds’.

(Hippocrates, 1881, p. 1)

Before exploring how popular depictions of sickness and space impacted health tourism, it must be noted that a Hippocratic view of illness was commonplace (Bryder, 1996, p. 454). Even after Robert Koch discovered the Tuberculosis (TB) causing germ Mycobacterium tuberculosis in 1882, TB treatment remained grounded in miasma theory (Sakula, 1983, p. 128).

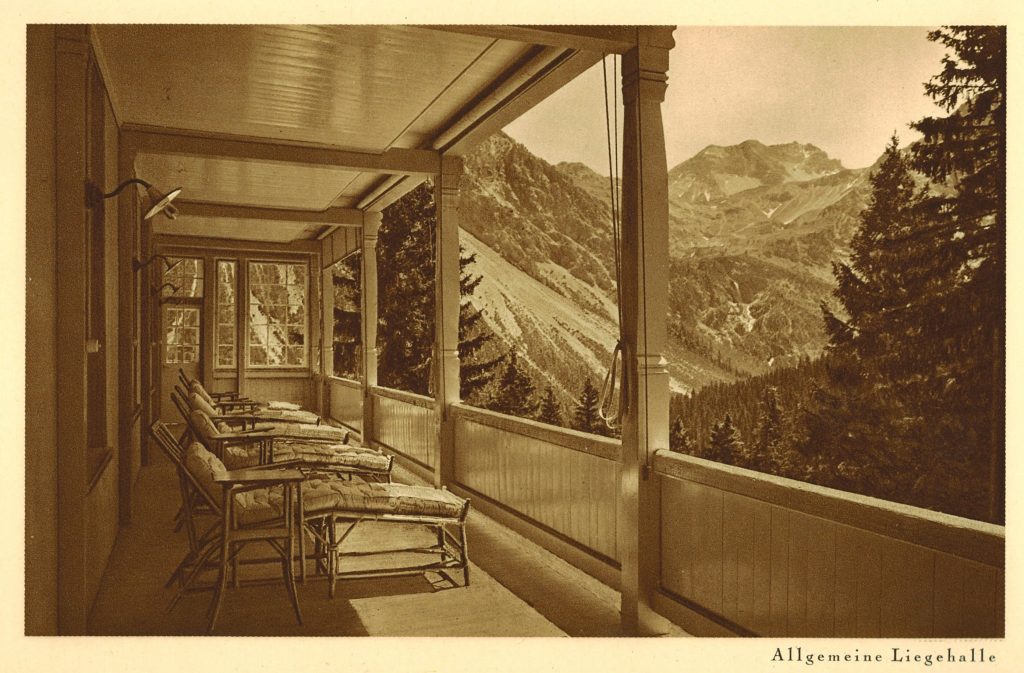

It was thought that TB could be cured by clean air, nutritious food and a strong spirit. German physician Dr von Jaruntowsky (1877, p. 16) recommended that invalids lay in the open air and participate in ‘methodical hill-climbing’. In the preface to the English edition of the book, Jaruntowsky urges Britons ‘to deal with Consumption as a curable disease’ (Jaruntowsky, 1877, p. 3). This idea that all diseases were curable reinforced the air of mystery surrounding TB, as it eluded medical understanding and was, therefore, stylishly misunderstood.

Despite the practical application of climatological theory in TB healthcare, much of the appeal of altitude therapy came from the fusion of imaginative geography with the tubercular’s string of romantic literary depictions. When an 1881 medical textbook states ‘depressing emotions’ as a cause of TB, it seems inevitable that a pallid romantic should choose to spend their time in a picturesque Alpine resort (Dubos, 1952, p. 69). According to Susan Barton, the sanatoria’s popularity ‘emerged from a blending of the philosophies of romanticism and alternative medicine, later backed up by scientific investigation’ (Barton, 2008, p. 6). This is evident in much of the literature on mountaineering and consumption, which share overlapping themes of mystery, beauty, passion and spirituality.

Sontag (1978, p. 5) recognised that, unlike previous epidemic diseases such as the bubonic plague, which had tended to afflict entire communities, TB ‘was understood as a disease that isolates’ an individual. For example, sanatoria, which were clinics specifically designed for patients suffering from TB, functioned both as a hospital and a place of relaxation removed from the general population.

The Magic Mountain

As explored by Marjorie Hope Nicholson (1959) in her seminal work Mountain Gloom, Mountain Glory, the literary portrayal of the Alps evolved from a place of danger to a place of bliss throughout the eighteenth century. Propagated by improvements in transportation and commerce, the Alpine mountains became commercial hubs of health and spirituality (Frank, 2012, p. 197). English mountaineer Clinton Dent described the range as ‘a curious fascination for the solitary man’, providing him with the distance to meditate on his life (Dent, 1885, pp. 2-3). In Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain, the main character undergoes a spiritual transformation after the mountain air allows him to meditate on the true meaning of his existence (Mann, 1924).

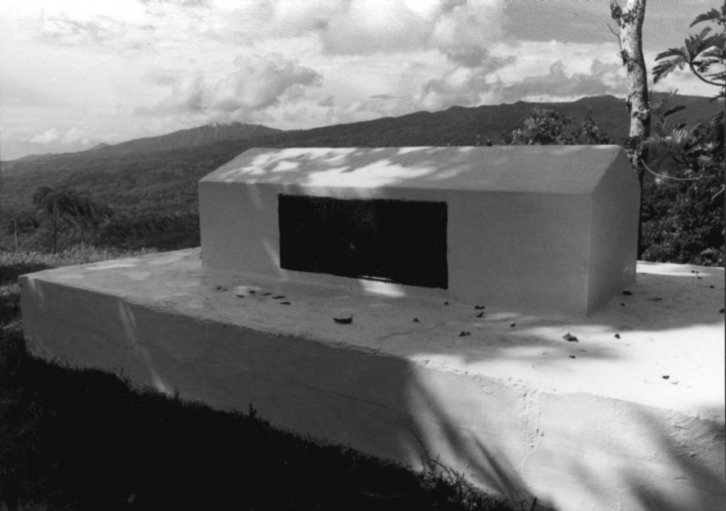

Similarly, when Scottish poet Robert Louis Stevenson began his impassioned pilgrimage before he was consumed by illness, he demanded to be buried on Mount Vaea, with the following poem as his epitaph:

‘Under the wide and starry sky,

Dig the grave and let me lie’.

All Consuming Phthisis

Known for prematurely killing poets, such as Anton Chekov, Franz Kafka and John Keats, to name a few, consumption was romanticised, gaining the similarly mysterious and attractive allure as the Alps. Death by consumption was beautiful, a burst of spiritual passion after months of wasting. Romantic poet Lord Byron recognised the disease’s charm, declaring: ‘I should like, I think, to die of consumption’ (Byron, n.d, cited in Clarke, 2019).

To die at the hands of the mountain was similarly appealing, as Clinton Dent was one of many mountaineers to write about the ‘impulse almost controllable to throw [himself] down’ the mountain after reaching the top (Dent, 1885, p. 216). These fantasies stem from the need to apply metaphoric thinking to the fearful concepts of death and danger, imbuing sickness and peril with romantic sentiment.

Mountaineering was seen as a rite of passage for the Romantic poet. In 1807, Lord Byron wrote that ‘the benefit of such pure air, or so elevated a residence, as might enable me to enter the lists with genuine bards’ (Byron, 1807). Here, he refers to the romantic bard, the wandering storyteller, who is spiritually impassioned to produce gifted poetry (Cusack and Norman, 2012, p. 404).

Artist John Ruskin, famously infatuated with the Alps, noted that the mountains had made him ‘weaker, more lifeless, more effeminate, more liable to passion’ (Ruskin, 1863). Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley depicted a similar portrayal of beautiful suffering in his poem Queen Mab, written whilst suffering from consumption (Shelley, 1813).

‘Yes! She will wake again,

Although her glowing limbs are motionless,

And silent those sweet lips,

Once breathing eloquence,

That might have soothed a tiger’s rage’.

The typical image of the consumptive was someone tragically young and strikingly beautiful. They were connected with ideas of passion and sexuality, noted by Sontag (1978, p. 2) as having a ‘liveliness that comes from enervation’ in the last stages of life. In her study of tuberculosis in Victorian literary imagery, Katherine Byrne (2011, p. 93) describes the consumptive as ‘dramatically pale and ethereally thin with the red cheeks and bright eyes of fever’. This was echoed by John Keats in 1819, who described death by consumption as ‘where youth grows pale, and spectre-thin, and dies’ (Keats, 1819). TB was a metamorphosis, where the childlike innocence disintegrates, leaving behind a sensual febrility.

Victorian literature not only linked consumption to images of eroticism and beauty but also depicted it as an aphrodisiac. This passion was prevalent at the high-altitude sanatoria, as in 1862 Conrad-Ahrens noted Davos’ ‘increase in the luxury of the female sex’ (Frank, 2012, p. 193). The very nature of consumption made the invalid aware of their desires.

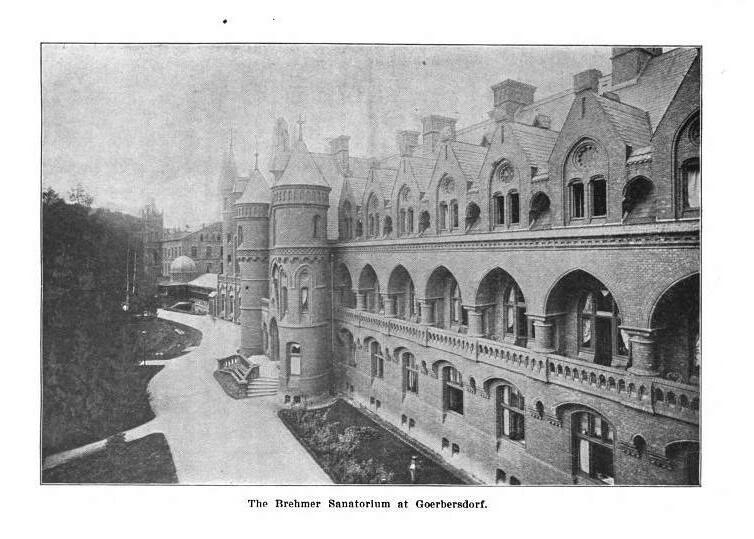

The Great White Plague

Tuberculosis was a disease that ‘consumed’ its victims, associated with severe weight loss and malnutrition. Depictions of the consumptive’s youth and beauty were often coupled with depictions of their hunger and desire (Jones, 2016, p. 17). English writer and politician Edward Bulwer-Lytton wrote fondly of his experiences eating and drinking whilst undergoing solitary water treatment for his succession of feverish illnesses (Bulwer-Lytton, 1851, p. 16). Understandably, one of the earliest mountain sanatoriums in Silesia, established in 1859, contained two extravagant dining halls (Bryder, 1996, p. 454). This was favourable for those who could afford it, as noted in 1907 by author Joseph Conrad, who described the Davos-Platz resort as ‘where the modern dance of death goes on in expensive hotels’ (Conrad, 1988, p. 420).

As Romantics criticised urban cities as being blighted and deprived, it seemed natural to flee to a more comfortable landscape. Consumptives needn’t be confined to small, hot rooms, too sick to eat, languidly spreading the disease to their loved ones (Frank, 2012, p. 189).

Although many Victorian tourists travelled for health rather than pleasure, caring for the mind was often as important as caring for the body. Furthermore, as Romantics wrote fondly of the countryside and the spiritual benefits of stepping away from the growing urban industry, mental and physical health connections grew stronger (Frank, 2012, p. 197). This was noted in William Coxe’s 1801 travel writings, which explored mountaineering as a sublimation of spiritual transcendence:

‘Lifted up above the dwellings of man, we discard all grovelling and earthly passions… and as the body approaches nearer to the ethereal regions, the soul imbues a portion of their unalterable purity’ (Coxe, 1801, p. 196).

This sort of psychic crusade is indicative of the romantic ideas around travel.

When considering the painful reality of TB, it is understandable why one may wish to distort it, to see beauty in the suffering and provide death with meaning. It explains why the sufferer may be drawn towards the cool mountain summit, depicted as a place of reckless extremes where the mind and body can be fused.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Bulwer-Lytton, E. (1851) Confessions and observations of a water-patient. [Online]. Available from: <https://wellcomecollection.org/works/s7arq9rc/items?canvas=2> [Accessed 24 February 2024]

Byron, G, G. (1807) Hours of idleness. [Online]. Available from: <https://archive.org/details/hoursofidlenesss00byro/page/n15/mode/2up> [Accessed 18 February 2024]

Conrad, J. and Karl, F, R. and Davies, L. eds. (1988) The Letters of Joseph Conrad: Volume 3, 1903-1907. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cooper, R, T. (1912) A sickly young woman sits covered up on a balcony; death (a ghostly skeleton clutching a scythe and an hourglass) is standing next to her; representing tuberculosis. [Watercolour] Held at Wellcome Trust.

Coxe, W. (1801) A Historical Tour in Monmouthshire. London: T. Cadell and W. Davies.

Dent, C, T. (1885) Above the Snow Line: Mountaineering Sketches Between 1870 and 1880. London: Longmans Green and Co.

Giles, R, H. (1820) A girl reads to a convalescent while a nurse brings in the patient’s medicine. [Watercolour]. Available from: Wellcome Collection.

Keats, J. (1819) Ode to a Nightingale. [Online]. Available from: <https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44479/ode-to-a-nightingale> [Accessed 8 March 2024]

Knopf, S, A. (1854) The Brehmer Sanatorium at Goerbersorf. [Online]. Available from: <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Brehmer_sanatorium.jpg>

Mann, T. (1924) The Magic Mountain. Berlin: S. Fischer Verlag.

Munch, E. (1907) The Sick Child. [Oil Painting]. Held at The Tate.

Peter, S. (n.d.) Allgemeine Leigehalle. [Photograph]. Available from: University of Zurich.

Robinson, H, P. (1858) Fading Away. [Photograph]. Held at The Met.

Shelley, P, B. (1813) Queen Mab. [Online]. Available from: <https://www.marxists.org/archive/shelley/1813/queen-mab.htm> [Accessed 28 February 2023]

Stevenson, R, L. (1880) Requiem. [Online]. Available from: <https://www.scottishpoetrylibrary.org.uk/poem/requiem/> [Accessed 23 February 2024]

Wellcome Collection (1831) A young woman of Vienna who died of cholera, depicted when healthy and four hours before death. Coloured stipple engraving. Available from: <https://wellcomecollection.org/works/vt5g3jxf>

Secondary Sources

Bainbridge, S. (2020) Mountaineering and British Romanticism: the literary cultures of climbing, 1770-1836. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Barton, S. (2008) Healthy living in the Alps: The origins of winter tourism in Switzerland, 1860-1914. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Bryder, L. (1996) “A Health Resort for Consumptives”: Tuberculosis and Immigration to New Zealand, 1880-1914. Medical History, 40 (4) October, pp. 453-471.

Byrne, K. (2011) Tuberculosis and the Victorian Literary Imagination. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Clarke, I. (2019) Tuberculosis: A Fashionable Disease? [Online]. London: Science Museum. Available from: <https://blog.sciencemuseum.org.uk/tuberculosis-a-fashionable-disease/#:~:text=Romantic poet Lord Byron wished,’”> [Accessed 24 February]

Cusack, C, M. and Norman, A. (2012) Handbook of New Religions and Cultural Production. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill Publishers.

Dubos, J. (1952) The White Plague. New York: Little, Brown, and Company.

Frank, A, F. (2012) The Air Cure Town: Commodifying Mountain Air in Alpine Central Europe. Central European History, 45 (2) June, pp. 185-207.

Jones, G. (2016) ‘Captain of All These Men of Death’: The History of Tuberculosis in Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Ireland. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill Publishers.

Hippocrates (1881) Hippocrates on airs, waters, and places. London: Wyman & Sons.

Jaruntowsky, A, V. (1877) The private sanatoria for consumptives and the treatment adopted within them. Rebman: London.

Nicholson, M, H. (1959) Mountain Gloom, Mountain Glory: The Development of the Aesthetics of the Infinite. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Sakula, A. (1983) Robert Kock: Centenary of the Discovery of the Tubercle Bacillus, 1882. Can Vet J, 24 (2) April, pp. 127-131.

Sontag, S. (1978) Illness as Metaphor. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.