By Elliot Travis

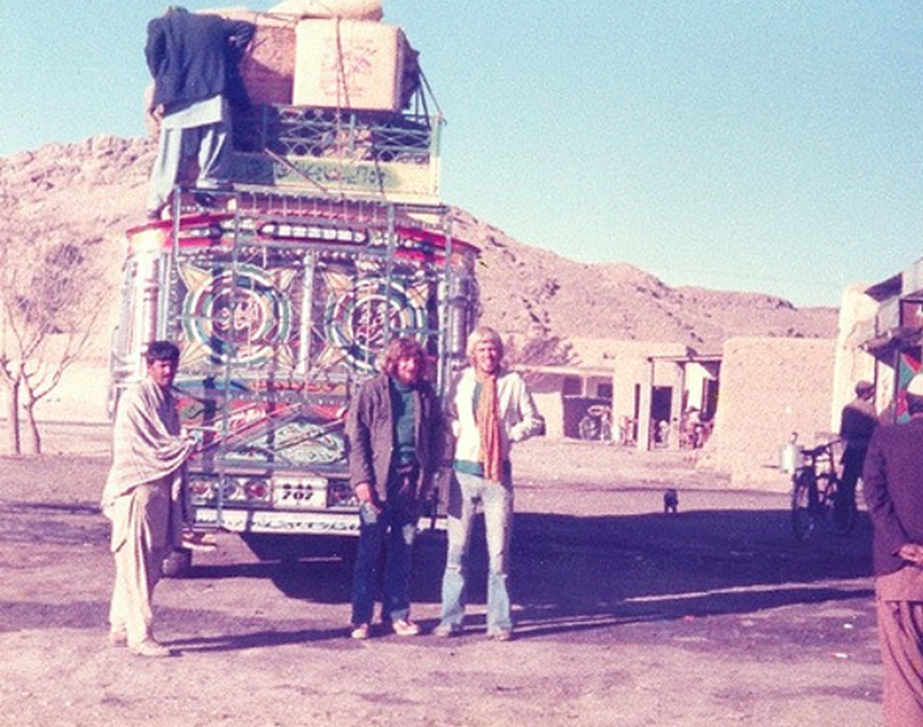

A group of travellers stood outside their campervan in Asia.

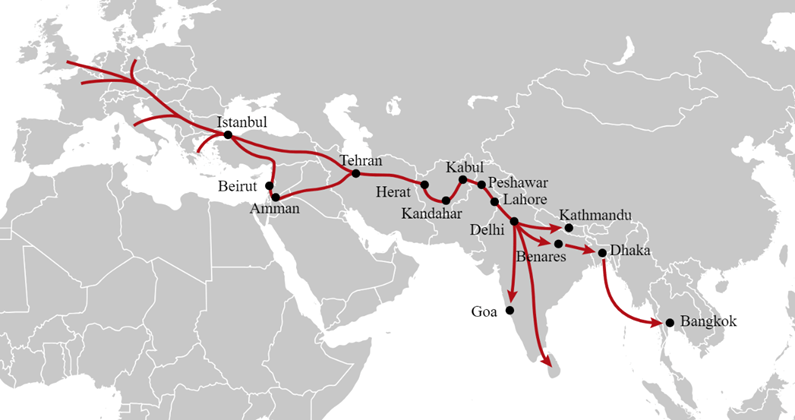

As we saw in the previous blog post, most Brits travelled to places with lots of sun and beaches and chose package holidays. However, there was a minority that looked for an alternative, one of which was the Hippie Trail. Little routes were as enticing as the Hippie Trail in modern travel and tourism history. From the late 1960s to the 1970s, the trail from Europe to Asia thrived amongst many younger British travellers and people from other countries in Europe, Australia, and North America. Some teenagers and young adults in this era wanted a unique lifestyle, wanting to break away from society and have freedom. The typical route through Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan, and Pakistan to India was not hampered by later wars and political conflicts, and it was possible to travel northwards to Kathmandu (Oliver, 2014, p.143). Seeking cultural exchange was among many factors to people choosing to travel across the hippie trail, with the appeal of drugs becoming a significant factor towards the 1970s. Was it just the appeal of drugs that made this trail famous with younger people? This blog will focus on that question, analysing how significant learning new cultures and beliefs was in their decision.

Map of the hippie trail route.

Defining Hippie and the spiritual attraction to the Hippie Trail:

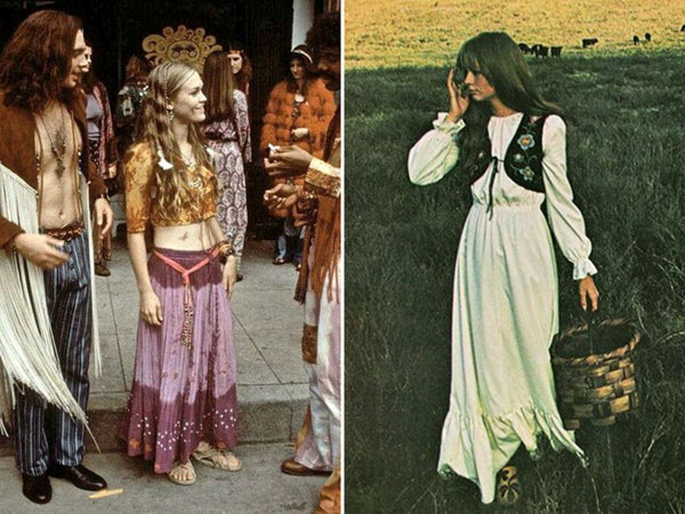

Hippie Fashion from the late 1960s to the 1970s.

The origin of the term ‘hippie’ is uncertain, but it was broadly designated that if someone was referred to as ‘hip’, they would be seen as trendy and fashionable and have a very relaxed approach to life (Oliver, 2014, p.18). While in some ways making the complete break from mainstream society, Hippies did nothing to reform their societies further, and the counterculture was made up of many very varied subcultures (Marwick, 2012, p.13). Hippies typically came from white, middle-class families in developed societies and were a minority in their culture as they wanted more freedom and fewer restrictions within it (Dallen and Zhu, 2021, p.211). The Overland route (another name for the Hippie Trail) was a perfect experience because they knew everything would be fine when they returned home because of their middle-class status. Arguably, the hippie belief could be that they did not believe in anything where they would be seen as running away from something and running to another.

Part of the hippie style was to be unique, and cultural artefacts from India became a crucial part of their fashion (Oliver, 2014, p.38). String beads were the most common artefact worn by the hippies as they acted as an aid in meditation for Buddhist and Hindu cultures, which the hippies adopted (Oliver, 2014, p.38). As the beads became popular amongst the hippie population in the West, more artefacts began to be recognised as good fits for the counter-cultural hippie lifestyle, so kaftans and shoulder bags became new and popular items (Oliver, 2014, p.38). With these becoming part of the culture, the hippie trail became more popular as hippies would travel to seek new artefacts for their fashion and embrace new cultures to feel the importance of what they wore to the Hindus or Buddhists. Girls adopted the fashion culture of the Hindus, and this was shown in Patrick Marnham’s travels when the girls he met on his travels would buy silk dresses, beads, rings and bracelets to show off to people at cannabis parties (Marnham, 2005, p. 121). When people decided to travel along the hippie trail, they had very little knowledge due to the lack of travel guides and depended heavily on stories and advice from others who had done it and people along the way (Oliver, 2014, p.144).

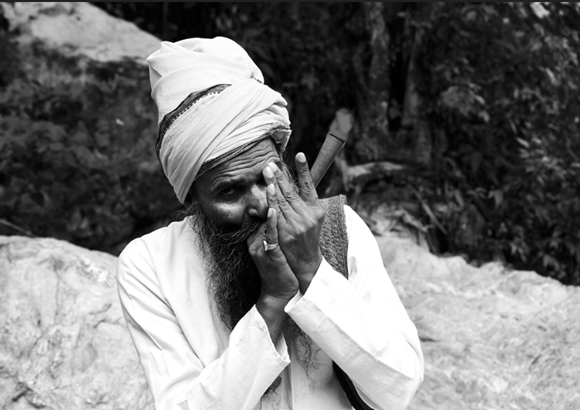

Indians are wearing the beads that hippies adopted to their fashion.

The artefacts collected were paired with the hippies’ ‘flower power’ philosophy, which they adopted because they realised that all human beings are interested in the planet’s state (Oliver, 2014, p.118), so the combination of these represented their counter-cultural beliefs. One hundred years earlier, similar actions were taken by travellers who attempted to cross the Overland route from European countries. They would attempt to carry flowers, birds’ feathers and shells across with them to keep as reminders of their journeys (Maddrell, Terry and Gale, 2015, p.155).

The hippie ‘flower power’ fashion.

To say that the Hippie trail was a pilgrimage is contested. Whilst lots of young people travelled to places like Kathmandu and India to embrace cultures and beliefs, many returned home with no change in belief and only adopted certain aspects of the new cultures they learnt, such as wearing beads they had collected and continuing to smoke and do drugs. In cases like Jasper Newsome’s, on return to England, he continued to smoke cannabis, which got him arrested (Tomory, 1996, p. 90). He read Orientalia, which led to him failing exams, so he was sent back to India to live legally (Tomory, 1996, p. 90).

How Drugs shaped the Hippie Trail experience:

Along the Hippie Trail, when interacting with Hindus in particular, hippies would often try cannabis as it was associated with the worship of the God Shiva and would be used in religious rituals, most likely in India (Oliver, 2014, p.76). A chillum pipe would be used to inhale the cannabis, and because of how popular this was to hippies, they would often bring these back to their homes to keep as souvenirs from India (Oliver, 2014, p.77). This reminded them of the rituals they took part in on their travels. When travellers set off across the trail, they usually had very little money, between £50 and £100 and most would stick to this amount to gain the whole experience. However, if they ran out, they would draw on the pavements for money or sell their blood to hospitals (Gemie and Ireland, 2017, p.33). However, most travellers would become drug dealers or mediators in drug deals, as this was their most accessible way of making money.

A French 29-year-old man, Charles Duchaussois, arrived in Kathmandu along the north of the hippie trail. After one stroll around Kathmandu, he realised he could easily make money there and became a mediator for drug deals (Gemie and Ireland, 2017, p.34). He was not a hippie, but he lived amongst them and in Kathmandu, he noticed that many of the travellers had no spiritual motivation among them; he only saw their mindless consumption of drugs (Gemie and Ireland, 2017, p.34). It makes you wonder whether the hippie’s reasons for travelling across the trail was the lure of drugs, as they were legal in most places, and with it being part of Hinduism’s spirituality, you would be accepted by them. It suggests their priorities were not on learning the cultures and beliefs of the Hindus but on the consumption of drugs. When Jasper Newsome was travelling on the trail, he claimed he felt incredibly alienated from all but the well-educated Indians and found Hinduism childish and comic (Tomory, 1996, p. 89). However, after he had “Accidentally” smoked cannabis with poor, uneducated folk, it changed his feelings, and he began to embrace the temple shrines and their culture (Tomory, 1996). This is a clear indication that the impact of drugs on understanding cultures and feeling a part of them for travellers was massive and that without this, the experience may have looked a lot different for them.

Indian man smoking from a chillum pipe.

An escape from ongoing political tensions and the influence of the Beatles:

The decade from 1969 to 1979 saw a lot of political tensions as the Cold War reached its peak, so to escape this, young people travelled along the hippie trail. People from North America and Britain viewed this as a great way to enjoy some freedom. The countries along the trail mostly enjoyed political stability during this decade, with only the 1971 Indo-Pakistan War in the fight for an independent Bangladesh as the only outlier (Oliver, 2014, p.144). Apart from that, overseas people were accepted by the indigenous inhabitants of the areas they passed by (Oliver, 2014, p.144).

In 1968, the Beatles stayed at Maharishi’s Ashram in India, and this visit led many people from Britain and Australia to want to travel to India as they were intrigued as to why the Beatles travelled there. The Beatles had learnt of the uniqueness of Eastern music and were drawn to how they used to write songs whilst smoking cannabis or on drugs. All the Beatles members matched the hippie stereotype as they had long hair and beards and sought spiritual growth. Their trip to India inspired two of their songs, “Mother Nature’s Son” and “Dear Prudence”, which could suggest that although they went to India intending to learn about spiritual beliefs, they selfishly wanted to use the trip as inspiration for new music, contrasting the idea of a spiritual pilgrimage.

Concluding Thoughts:

Overall, the spiritual and cultural aspects that the Hippie trail offered were most exciting for young people from North America and Britain when planning their travels. The similarities drawn between the Hindus and the hippies who travelled critically impacted the fashion of hippies in Britain and their counter-cultural lifestyle. Drugs were part of Hindu spiritualism, and with this being adopted by hippies on the trail and taken back to Britain, this could stimulate the beginning of the drug problem that is still in Britain today. The people who returned to their homes acting like the Hindus they met on the trail, like smoking cannabis, suffered and would return to places like India to live. However, most people did not adopt the spiritual beliefs of Hinduism when they returned, but the artefacts they brought back, like the beads, suggest they did this to keep memories of an unforgettable trip.

Bibliography:

Images:

Wikipedia (2013) Routes of the Hippie Trail. [Online Image]. Available from: < https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hippie_trail#/media/File:Hippie_trail.svg > [Accessed 8 April 2024].

Primary Sources:

British Pathe (2014) Rishikesh – Beatles With The Maharishi (1968). [Online Video]. Available from: < https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aLeBZjPOJ-c > [Accessed 11 April 2024].

Flickr (2015) Ancient Indian style of smoking cannabis. [Online Image]. Available from: < https://www.flickr.com/photos/133630012@N05/19725846304 > [Accessed 11 April 2024].

Formidable Mag (2024) A group of travellers stood outside their campervan in Asia. [Online Image]. Available from: < https://www.formidablemag.com/hippie-trail/ > [Accessed 17 April 2024].

Manham, P. (2005) Road to Katmandu. London: Tauris Parke Paperbacks.

MyModernMet (2016) Hippie Fashion from the Late 1960s to 1970s. [Online Image]. Available from: < https://mymodernmet.com/vintage-bohemian-fashion/ > [Accessed 8 April 2024].

Open Magazine (2021) The Hippy Gaze. [Online Image]. Available from: < https://openthemagazine.com/columns/the-hippy-gaze/ > [Accessed 8 April 2024].

Revival (2020) Collage of Women in Hippie Outfits. [Online Image]. Available from: < https://revivalvintage.co.uk/blogs/news/guide-to-vintage-1970s > [Accessed 8 April 2024].

Tomory, D. (ed.) (1996) A Season in Heaven: True Tales from the

Road to Kathmandu. Thorson’s Publishing.

Secondary Sources:

Dallen, T. and Zhu, X. (2021) Backpacker Tourist Experiences: Temporal, spatial and cultural perspectives, In Sharpley, R. (ed.) The Routledge Handbook of Tourist Experience. London: Routledge, pp. 211-222.

Gemie, S. and Ireland, B. (2017) The Hippie Trial: A History. [Online]. Manchester: MUP. Available from: < https://academic.oup.com/manchester-scholarship-online/book/37352 > [Accessed 11 April 2024].

Maddrell, A., Terry, A. & Gale, T. (eds) (2015) Sacred Mobilities: Journeys of Belief and Belonging. [Online]. Farnham: Ashgate. Available from: < https://r2.vlereader.com/Reader?ean=9781472420084 > [Accessed 8 April 2024].

Marwick, A. (2012) The Sixties: Cultural Revolution in Britain, France, Italy and the United States, c.1958-c.1974. London: Bloomsbury.

Oliver, P. (2014) Hinduism and the 1960s. [Online]. London: Bloomsbury. Available from: < https://r1.vlereader.com/Reader?ean=9781472527653 > [Accessed 8 April 2024].