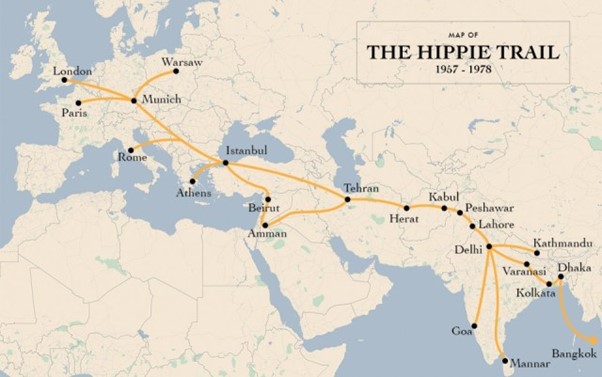

Beginning in London and ending most commonly in Kathmandu, the hippie trail, also known as the overland route, was a path through Europe and Asia that represented liberation “from the constraints of jobs, mortgages and social conventions” (Gemie, 2018, np). In other words, it was a way of leaving the Western world behind and moving across the land in search of transformation and self-discovery. However, the trail had its own social conventions and culture, which dictated a hierarchy among those who travelled the route. Some were considered inauthentic due to their means of travel and intentions on the road. Those who were more conventionally guided either via guidebooks, travel agents or tour buses were disdained as ‘tourists’, a label that was used in the pejorative, and intended to encapsulate the lack of ‘authenticity’ of those who held on to the supposed comforts of the West. This blog post will look at this debate and consider the supposed ‘authenticity’ of the traveller’s journeys, some of the differences between ‘tourist’ and ‘traveller’ and what performances distinguished them on the hippie trail, if there was any distinction between them at all.

SEARCHING FOR IDENTITY

The ability to travel along the overland route, somewhat safely, lasted for approximately a decade, between 1965 and 1978, and was popularised as part of the hippie counter-culture movement that developed during this period. The hippie movement was a ‘rejection’ of Western consumerism and led to elitism along the trail. Brian Ireland (2021) explains that traditional tourism, dictated by travel agents and tour guides, was “viewed as a symbol” of the culture they were trying to leave behind (Ireland, 2021, np). The people who moved along the routes declared themselves ‘travellers’ and as such distinguished themselves as separate from other Westerners in the East, who were disdained as ‘tourists’ due to their being “unthinking consumer[s] with no sense of discovery” (Gemie & Ireland, 2017, p.103). The reasons for following the route were varied, with some chasing dreams, others discovering themselves, and some simply pursuing something different “from the perceived monotony of middle-class life in Europe” (Sobocinska, 2014, np.) However, whatever their reasons, as Arne Walderhaug tells in his travelogue, one of the main cultural performances was to travel along the route as cheaply as possible to extend the journey (Walderhaug, nd, np). This included rejecting transportation methods traditionally used when travelling long distances such as airplanes or boats, unless strictly necessary. The methods of movement preferred were walking, hitchhiking, driving and buses, including tour buses.

TOUR BUS TRAVELLERS?

The hippie trail, for all its travellers’ scorn of the word ‘tourist’, generated an industry in the small tour bus companies that travelled along the overland route, offering inexpensive tours where other like-minded individuals would be able to travel together in relative safety. One such company was Swagman Tours (as the image above shows), which offered travel “from London to Kathmandu and back” and whose passengers looked and acted “like young Western tourists” but still considered themselves travellers (Gemie & Ireland, p. 101, 2016). As this documentary, The Road to Kathmandu (1975), shows, those who travelled on the route were mostly white and, in their twenties. They travelled along the same route with the same predetermined stops at sites of cultural significance. To reject Western culture, and yet still utilise inherently Western services and comforts, such as those represented by the tour bus, would appear to be hypocritical and antithetical to the spirit of the trail. However, those who used the buses believed themselves to be travellers regardless of this distinction, and Gemie and Ireland (2016) thought that the division between what constituted a traveller, and a tourist on the hippie trail could have been as simple as the belief in being a traveller (Gemie & Ireland, 2016, p. 103).

The travellers of the trail were “united in their rejection of the label ‘tourist’”, which included the search for ‘authentic’ experiences “through a range of performances that signalled their ‘authenticity’” and it was this uniting ideology that defined them (Gemie & Ireland, 2016, p. 103; Sobocinska, 2014, np.). However, Dean MacCannell (1999) noted that ‘authentic experiences’ inside cultures not your own, were merely “staged authenticity” because it was not “so easy to penetrate the true inner workings” of other cultures as there was an element of the performative that was based on visitor expectations (MacCannell, 1999, pp. 94-95). These expectations were proliferated through media such as the documentary linked above, word of mouth, and even the iconography associated with the hippie movement. This suggests that the distinction between tourist and traveller is simply the difference between the experience of how movement was achieved and the destination once movement occurred. One, the tourist, sought places to visit, a guided tour, in relative comfort, around monuments of cultural significance. Whereas the other, the traveller, sought people and approached movement across the land as an anthropological journey. This would indicate that the traveller on the hippie trail was merely a tourist of people and culture, in the same way that the tourist was a traveller of monuments.

PROGENITORS OF THE MAINSTREAM

Historians such as Agnieszka Sobocinska (2014), propose that the European traveller in Asia was a benefactor of the old colonial infrastructure in places like India and, in fact, extended “the long genealogy of imperial travel” to the present day, which would not have been possible if they weren’t Western (Sobocinska, 2014, np.) While this blog does not have the space to completely explore this statement, what can be said is that the European travellers through Asia were complicit in the booming tourist industry in the Asian continent. They were the sellers of fabrics, creators of tour guides like the Lonely Planet guidebooks, and advice pamphlets, and they were the progenitors of the ’mainstream’ backpacking tourist industry that had economic, cultural and environmental ramifications on the places they visited. The travellers were ‘developer tourists’ who utilized already existing infrastructure to provide or develop services for the next wave of travellers or ‘backpackers’ (Hampton & Hamzah, p.558, 2016). Rory Maclean gave an example of a patisserie in Istanbul that became the unofficial first meeting point of the trail (Maclean, np, nd). This shop, The Pudding Shop, was adopted by the trailgoers as the “information central” of the trail and was one of many instances of tourists appropriating an area for their own purposes. “Freak Street” in Nepal offered legally available drugs to travellers, and ashrams in Goa became a “hotbed of alternative culture” where people could meditate and “attempt to discover themselves” (Openskies, nd). By having these set destinations, printed in guidebooks and spread through notice boards and word of mouth, those who travelled the trail were acting in the capacity of the ‘tourist’ they so clearly disdained. They were not ‘discovering’ and not experiencing ‘authenticity’ in the way they claimed they were.

CONCLUSION

Those who moved along the trail created a hierarchy of travellers, with tourists being at the bottom of the list. However, when looking at the behaviours of the travellers along the hippie trail, including how they travelled, and how they appropriated culture and places as their own, we can see there was little distinction between the two. The exception, as shown above, was simply in the belief that they were travellers and not tourists because to them to be a tourist represented all that was wrong with the Western world they had left behind. Nevertheless, just because they moved out of the theoretical “West” does not mean they did not take the ideologies with them. They generated industry both at home and in places they were visiting, they were consumers and sellers who were hypocritically part of a system that was developed because of and for them. The supposed ‘authenticity’ of their experiences was questionable because the experience they wanted was performative based on their already preconceived notions of what the authentic nature of a place was.

References:

Primary Sources

Exodus Adventure Travels (2015) The Road to Kathmandu- Documentary (1975). [Online Video}. Available from: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9VzS0MQw1wU> [Accessed: 12 April 2024].

Shaahy, S. (nd) Overland Guide to Nepal. [Online] Available from: <https://www.richardgregory.org.uk/history/last-whole-earth-guide-1971.jpg> [Accessed 17 April 2024].

‘Swagman overland bus, Kabul, 1970’ (1970) Swagman overland bus, Kabul, 1970. [Online Image]. Available from: <https://www.messynessychic.com/2014/03/11/road-trip-to-afghanistan-snapshots-from-the-lost-hippie-trail/> [Accessed 12 April 2024].

Rory Macclean (c1967) ‘The Pudding Shop’. [Online Image]. Available from:< https://rorymaclean.com/hippie-trail/relive-the-journey/> [Accessed 17 April 2024].

Tomory, D. (ed) (1996) A Season in Heaven: True Tales from the Road to Kathmandu.

Travellers (nd) Five travellers on the Hippie Trail. [Online Image] Available from: <https://openskiesmagazine.com/the-rise-and-fall-of-the-hippie-trail/> [Accessed 15 April 2024].

Map of The Hippie Trail (nd) Map of the Hippie Trail, 1957-1978. [Online Image] Available from: <https://1960sdaysofrage.wordpress.com/2018/09/07/hippie-trail/> [Accessed 14 April 2024].

Walderhaug, A (nd). ‘Travelling the Hippier Trail’. [online] Available from: <https://www.walderhaug.org/travelogues/the-hippie-trail-ii> [Accessed 12 April 2024].

Secondary Sources:

Butterfield, M. (2020) ‘Full of Eastern Promise Part 1: Afghans, Kaftans and the Hippie Trail’. C20 Vintage Fashion. [Online] Available from: <https://www.c20vintagefashion.co.uk/post/full-of-eastern-promise-part-1-afghans-kaftans-and-the-hippie-trail> [Accessed 15 April 2024].

CNN (2022) The road trip that inspired the Lonely Planet guidebooks. [Online Video]. Available from: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VnS6HuGi6VQ&t=54s> [Accessed 12 April 2024].

Gemie, S. (2018) ‘The hippie trail and the question of nostalgia’. OUP blog. [Online] Available from: <https://blog.oup.com/2018/01/hippie-trail-question-nostalgia/> [Accessed: 13 April 2024]

Gemie, S. & Ireland, B. (2017) The Hippie Trail: A History. Manchester University Press: Manchester.

Hampton, M.P. & Hamzah, A. (2016) ‘Change, Choice, and Commercialization: Backpacker Routes in Southeast Asia. Growth and Change, 47 94) December, pp. 556-571.

Ireland, B. (2021) ‘The hippie trail: a pan-Asian journey through history’. History Extra [Online] Available from: <https://www.historyextra.com/period/20th-century/what-is-hippy-trail-asia/>

MacCannel, D. (1999) The Tourist. A New Theory of the Leisure Class. University of California Press, Ltd: London.

Sobocinska, A. (2014) ‘Following the “Hippie Sahibs”: Colonial Cultures of travel and the Hippie Trail’. Journal of Colonialism and Colonial History, 15 (2) Summer. [Online] Available from: <https://muse-jhu-edu.leedsbeckett.idm.oclc.org/article/549514> [Accessed 12 April 2024].

‘Stylistic Origin of Kashmiri Artistic Traditions’ (nd) UNESCO. [Online] Available from: <https://en.unesco.org/silkroad/content/cultural-selection-stylistic-origins-kashmiri-artistic-traditions> [Accessed 15 April 2024].

‘The rise and fall of the Hippie Trail’ (nd.) Open Skies Magazine. [Online] Available from: <https://openskiesmagazine.com/the-rise-and-fall-of-the-hippie-trail/> [Accessed 15 April 2024].