‘Curiosity about the patients doesn’t erase stigma; it perpetuates stigma. Sneaking around asylums diminishes the lived experience of the patients who suffered in there. It’s not OK to lie in someone else’s coffin or wear someone else’s straitjacket’ (Yanni, 2010).

The Historical Madhouse and its Treatments

Meaning a ‘place of refuge’, the historical mental asylum is the ancestor of modern day psychiatric hospitals, and its institutional roots can be traced as far back as 1247, in London. Originally named the New Order of our Lady of Bethlehem, the hospital would undergo four regenerations before settling in its current location of Beckenhem, yet it will never shake its well known nickname: Bedlam, now a byword for mayhem or madness. Prior to the opening of such institutions, those with mental illness and learning disabilities would be cared for by their families, and when the families could not provide that care, they would end up most likely destitute, homeless and begging for food and shelter.

By the 18th century, private institutions started to emerge but as Bazar & Burman point out, the patients in these institutions were more than likely the powerless wives of bored and jealous aristocrats, who would be forced into institutions no better than human zoos (Bazar & Burman, 2014).

Yet despite the age of psychiatric inpatient treatment, prior to the 19th century there was no real set treatment for mental illness, and for centuries the preferred treatment would change alongside other trends of the day.

Some notable examples are trephination, bloodletting and of course, lobotomies. Each of these ‘treatments’ revolved around removing something from the body – either a part of the skull to release pressure on the brain, or blood, bile, and vomit to re-balance the humours, or removing the connection between parts of the brain – yet no move was made to change the environment in which the person lived, or to make changes to their lives.

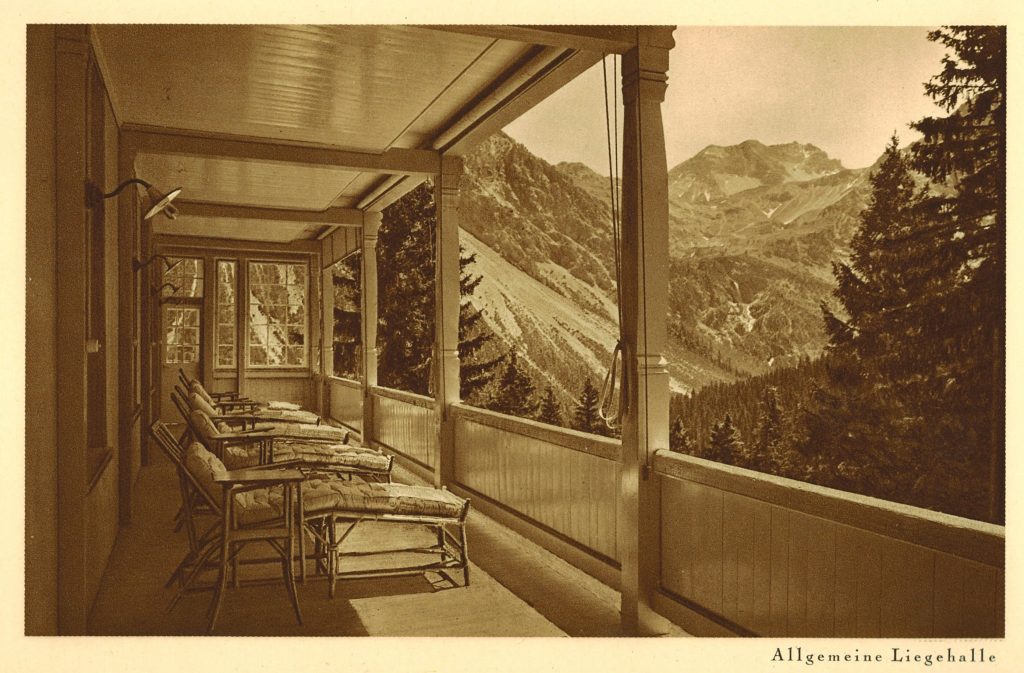

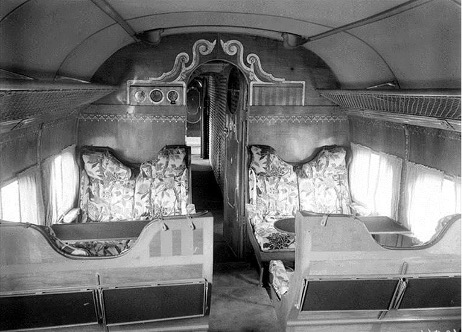

Thus enter, the ‘moral treatment’. For the first time, mental illness was seen as a curable disease, the depletion of one’s mental energies leading to insanity, and the cure was… almost simple, compared to past methods – it could be broken down into five things: rest, meaningful employment, appropriate amusements, hygienic conditions and, most importantly, kindness.

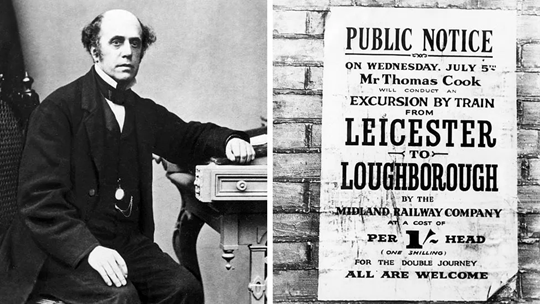

If you had wanted to visit an asylum in the 19th century, you would need to purchase a guidebook such as Miller’s New York As It Is, or the Englishman’s Illustrated Guide to the United States and Canada, and you would have to physically travel to the institutions, and pay to walk through them, a costly endevour. Instead, a simple search on YouTube offers thousands of videos ranging from millions of views to barely a thousand that you can watch from the comfort of your own home.

The Tourist and the Asylum

As mentioned above, the Victorian tourist would require guidebooks for their visits to new cities and towns, and more often than not these guidebooks recommended asylums as a must-see destinaiton. For example, Miller’s New York recommended visiting twelve different asylums within the city, whilst the Englishman’s Illustrated Guide recommended at least twenty-one.

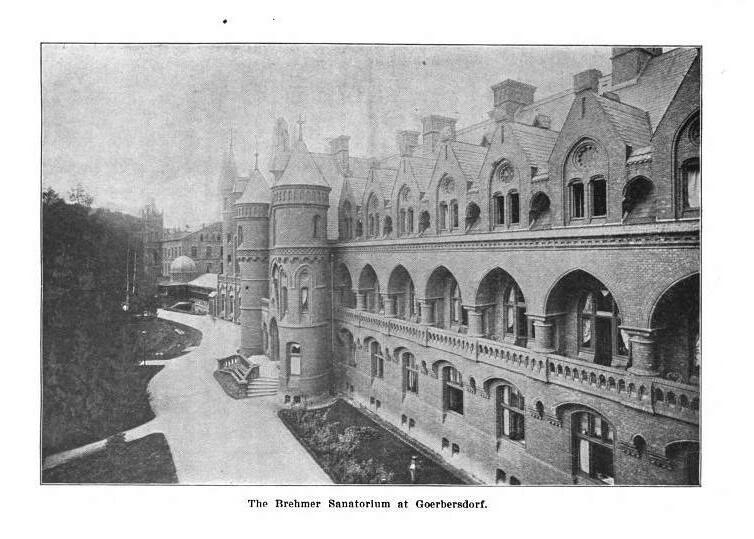

One asylum Miller recommends is the Bloomingdale Asylum for the Insane, as shown above, located in the Morningside Heights neighbourhood of Manhattan. Miller’s As It Is marks a move from interest in asylums for their patients, and interest in asylums for their architecture and landscaping – a move from the mentally ill, to manicured lawns.

Miller’s guide describes the approach to the asylum from the southern entrance as ‘highly pleasing’, and continues to say that ‘the sudden opening of the view, the extent of the grounds, the various avenues gracefully winding through so large a lawn. … The central building … is always open to visitors, and the view from the top of it being the most extensive and beautiful of any in the vicinity of the city, is well worthy of their attention’ (Miller, 1880, p. 46-47).

The shift in a more focused, set treatment also meant a shift in the way asylums are viewed – thus, every element of the institution was an integral part of treatment, both inside the building and out of it, and so visitors were encouraged to visit the gardens, and take in the beautiful buildings. No longer were people coming to view the patients, but instead to view the asylum – Jane Miron, author of ‘Prisons, Asylums and the Public’ argued that for asylum administrators, encouraging tourism became a way of gaining public support and confidence – it would also help to discourage the scepticism of treatment and the stigma surrouding mental illness (Miron, 2011).

But have we really left asylum tourism behind? Or has it simply changed formats?

A Move to Modern Voyeurism

Bazar & Burman write that the practice of asylum tourism may seem strange and uncomfortable to 21st century readers, but I would like to argue that we still hold fascination with asylum tourism, and that not only does it still exist, that it has simply changed forms and it some ways, become even more accessible than its predecessors, and even more voyeuristic.

Although it primarily holds sexual connotations, to be a voyeur and to be voyeuristic also extends to the interest and enjoyment of other peoples suffering and misery, and is that not the very basis of asylum tourism?

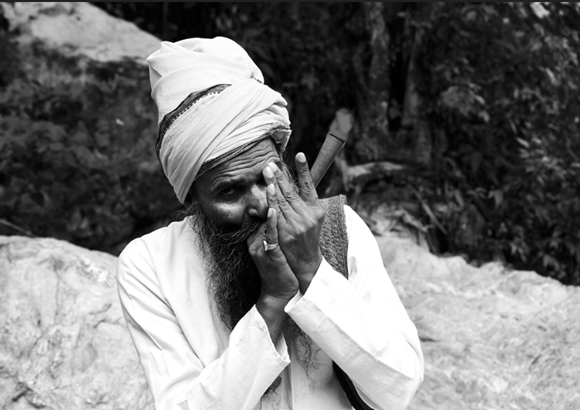

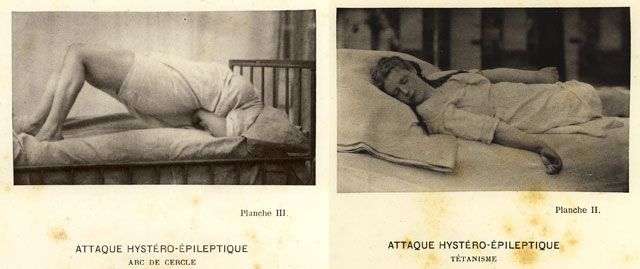

The use of photography in asylums and psychiatric hospitals is not a new one, its use can be traced back to the 1870s with clinicians Henri Dagonet and Jean-Martin Charcot as some of the first to make use of it as a diagnostic tool (Eghigian, 2010). Their diligent work in photographing patients experiencing hysteria allowed for the creation of diagnostic criteria for maladies of the mind.

While the image above is an example of photography to be used in aid of diagnostic criteria, it is still an example of the voyeuristic interest we hold with regards to asylums and their patients, in this case, we are still seeking some intrusive entertainment from another persons vulnerable moments in order to satisfy our own curiosity.

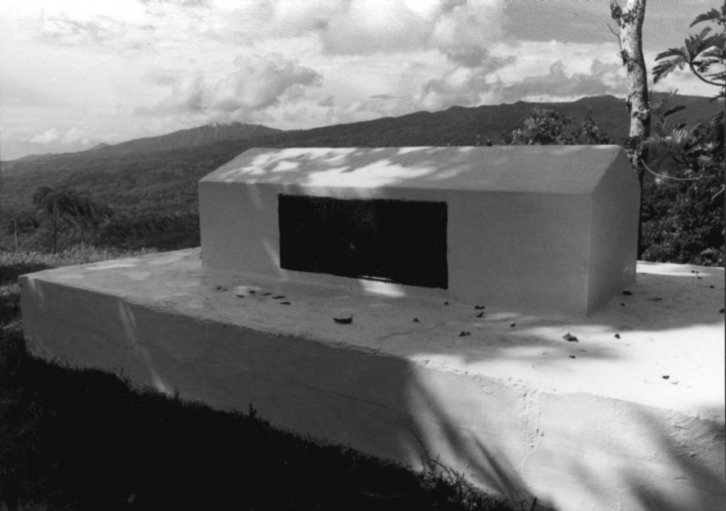

The relationship between asylums and photography continues even today, but now for new reasons – it is no longer used to document patients and their symptoms, but instead it is used to fulfil the voyeuristic curiosity that surrounds abandoned asylums and hospitals – a sentiment not dissimilar to the one held by our predecessors when presented with the opportunity to tour functioning asylums.

Not only do we embrace asylum tourism presented to us in accessible formats such as videos and photographs, we are still interested in touring the buildings themselves. Through companies such as Haunted Happenings, you can follow in your Victorian ancestors footsteps and book to tour asylums and hospitals for the price of £69 per person – with the added excitement of the paranormal, as its not enough to simply tour the buildings where people faced dehumanising and inhumane treatments, but we must be able to witness their continued suffering from beyond the grave! But its not just tours, its books which tell us the biographies of patients, and their illnesses and their subsequent fates – such as Voices from the Asylum: West Riding Pauper Lunatic Asylum by Mark Davis, and its podcasts such as Asylum Stories as available on Spotify which discusses hospitals, patient stories and treatments.

Closing Thoughts

As humans, we have always been interested in the macabre, the morbid and the unknown – we will always want to know whats behind the curtain, and asylums and mental hospitals only naturally fall into our path of curiosity – be it through physically touring the buildings, photography, videos, books or podcasts, we have a desire to know everything we can about taboo subjects.

Though original believe was that asylum tourism died out following the change from asylum to psychiatric hospital, I have aimed to show that not only is this not true, but our attitudes to psychiatric hospitals, psychiatry and the mentally ill are more voyeuristic than before.

References

Primary Sources

Englishman and Oxford University (1880). The Englishman’s illustrated guide book to the United States and Canada. (Centennial ed.). [online] Internet Archive. Available at: https://archive.org/details/englishmansillu00englgoog/mode/2up.

Miller, J. and The Library of Congress (1872). Miller’s New York as it is, or Stranger’s guide-book to the cities of New York, Brooklyn, and adjacent places .. [online] Internet Archive. New York, J. Miller. Available at: https://archive.org/details/millersnewyorkas00mill/page/42/mode/1up?view=theater.

Secondary Sources

Bazar, J.L. and Burman, J.T. (2014). Asylum Tourism. https://www.apa.org. [online] Feb. Available at: https://www.apa.org/monitor/2014/02/asylum-tourism.

Box, C. (2021). 19th-Century Tourists Visited Mental Asylums Like They Were Theme Parks. [online] Ranker. Available at: https://www.ranker.com/list/asylum-visitors-in-the-nineteenth-century/christy-box.

Chambers, P. (2020). Bethlem Royal Hospital: Why Did the Infamous Bedlam Asylum Have Such a Fearsome reputation?[online] HistoryExtra. Available at: https://www.historyextra.com/period/victorian/bethlem-royal-hospital-history-why-called-bedlam-lunatic-asylum/.

Coleborne, C. (2001). Exhibiting ‘Madness’: Material Culture and the Asylum. Health and History, 3(2), pp.104–117. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/40111408.

CSP Online. (2020). A History of Mental Illness Treatment. [online] Available at: https://online.csp.edu/resources/article/history-of-mental-illness-treatment/.

Eghigian, G. (2010). Who’s Haunting Whom? The New Fad in Asylum Tourism. [online] Psychiatric Times. Available at: https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/whos-haunting-whom-new-fad-asylum-tourism.

HauntedHappenings.co.uk. (n.d.). Haunted Asylums & Hospitals. [online] Available at: https://www.hauntedhappenings.co.uk/haunted-asylums-hospitals/.

Kahn, E.M. (2016). Chains, Whips and Misery: Studying and Preserving Old ‘Lunatic’ Asylums (Published 2016). The New York Times. [online] 29 Sep. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/30/arts/design/chains-whips-and-misery-studying-and-preserving-old-lunatic-asylums.html.

Miron, J. (2011). Prisons, asylums, and the public : institutional visiting in the nineteenth century. Toronto: University Of Toronto Press.

Narula, B. (2021). What It Meant to Be a Mental Patient in the 19th Century? [online] Lessons from History. Available at: https://medium.com/lessons-from-history/what-it-meant-to-be-a-mental-patient-in-the-19th-century-86340b93199b.

Ottin, T. (2022). What Was Life like in a Victorian Mental Asylum? [online] History Hit. Available at: https://www.historyhit.com/life-in-a-victorian-mental-asylum/.

Rondinone, T. (2021). Dark Places—Our History of Asylum Tourism | Psychology Today United Kingdom. [online] http://www.psychologytoday.com. Available at: https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/blog/the-asylum/202103/dark-places-our-history-asylum-tourism.

Science Museum. (2018). A Victorian Mental Asylum. [online] Available at: https://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/objects-and-stories/medicine/victorian-mental-asylum.

Yanni, C. (2010). Review – Forbidden Places: Online Photography Exhibit of the New Jersey State Hospital for the Insane. [online] h-madness. Available at: https://historypsychiatry.com/2010/08/09/review-forbidden-places-photograph-exhibit-of-the-new-jersey-state-hospital-for-the-insane/.

York, B. (2023). Inside The Haunting Past of 19th-Century Mental Hospitals. [online] History Defined. Available at: https://www.historydefined.net/the-history-of-19th-century-mental-hospitals/.

Images

Bloomingdale Insane Asylum in 1834. (n.d.). Available at: https://bloomingdalehistory.com/2016/01/10/the-bloomingdale-insane-asylum/.

Charcot, J.-M. (n.d.). Attaque Hystero-Epileptique. [Photography] Available at: https://hystoria.ca/2015/11/29/charcots-photography/.

Hogarth, W. (1734). A Rake’s Progress VIII: The Madhouse. [Oil on Canvas] Sir John Sloane’s Museum Collection Online. Available at: https://collections.soane.org/object-p47.