In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, what did young aristocrats do once they finished their education? It was in fact not much different to what happens today. Many of the wealthy upper-class children took years out to travel Europe. This kind of travelling carried on all the way until the Napoleonic wars, even then people travelled Europe, or even the UK. There were multiple reasons for the Grand tour, the outcome sometimes varied from the intention. According to James Buzard, “the Grand tour was from start to finish an ideological exercise.” (Buzard,2002, p38) These young men were sent away to learn the skill or art appreciation, as well as political competency. The side of the Grand tour that doesn’t get discussed as much is the idea that they went away to “sow their seeds” meaning that they went away to drink, have sex, and gamble to get it all out of their system in order to go back to England and run households or start their careers. In order to be prepared for their future careers they had to learn about how to be a man, especially a man in high places.

Aristocratic families had paid large sums of money for their children to go to school and university in order to gain a sound education that resulted in a career path adequate of an upper-class individual. On completion of university education, there was a period where parents felt their children needed to apply the knowledge they learned in school and other forms of education to real life. The languages taught in schools were, again, of an importance (Lyttleton, 1728). They could practice their language skills in these areas they were visiting to further their education. Which is basically what the whole point of embarking on the grand tour was for. All of these skills were viewed as masculine, they were needed in order to make the perfect gentleman who was capable of running estates and working in high places of government. Women on the other hand would not have had the same education (Sweet, 2015, p52). They would have not been taught to the level that males were. This then became more obvious in journals. Once women began also travelling around Europe there was more information to highlight the gap between them. Men had little interest in Antiques, they were more interested in areas of historical relevance and architecture, whereas women entered into more detail about these areas describing their beauty etc (Sweet 2015, p 36). This highlights a contrast between them, women probably had little knowledge about these things therefore were basically seeing it from a blank slate. In comparison, these men knew the histories behind them, this highlights the element of masculinity that was being portrayed throughout Europe.

This idea of males and females having different reactions to art and places of significance highlights the pressure that develops for the need to react in a certain way. As the Grand tour became more and more popular, still within the upper classes, there was an element of making sure you were doing the right thing. There was a need to react a certain way otherwise you weren’t doing the grand tour correctly, women reacted in one way and were worried about reacting too much like a man would and men were worried they had a too feminine response. Therefore, in trying to develop and become the most educated person, there was an element that you were also trying to fit into society, to grow to fit in. There was also a need to show off your knowledge and experience at home. There are examples throughout collections in England, especially in Ford’s collection (De La Rosa, 2015) of artwork that was commissioned in order to show off the level of travel and education they had achieved. They were commissioning the art to fit in with the antiquities that they were seeing. But the underlying factor was that they were showing off their masculinity. Men wanted to show how far they had got on the Grand tour, all of the travelling and living in different conditions, all built into their idea of being masculine.

In order to discuss politics, which was probably one of the main lines of conversation for upper class men, they needed to mix with men in politics and experience it first-hand. The whole idea of the Grand Tour was experiencing life, practicing before they do the real thing in England. In letters home to family members there is evidence of these young men mixing with highly politicised people in European states, they would send home information about what was going on (Lyttleton, 1728). Many journals discussed the political systems they had encountered. Italy was of special interest to British because they felt that as English people they were ‘New Romans’ they felt that they had a civilised society and were interested to see how different states tackled democracy and politics in general (In Our Time, 2002). Ultimately though, these young men were not interested particularly in the people they saw, the lower classes, the peasants in these areas. It was all about the political and historical relevance of the areas they were visiting. The integration of these young upper-class men into European political circles would go as far as spending time in courts such as, German, Iberian, Scandinavian and Russian states (…), highlights the extent to which they found out information. The interest in Italian politics was due to this idea that the English were civilised, and the rest of Europe was not (Black, 1985:2010, p114). They spent a lot of time deeply interested in how Italians ran their countries. Let me highlight here, that those who were in the courts experiencing these political situations were men. These men were learning how to become ‘men’ of influence and fit into the idea of masculinity that was being developed around this period.

However, was this all purely a front? Were these men actually living life in a completely different way than the letters sent to their parents? It is easy to see from experience that the majority of young people are not interested in history and politics therefore, how likely is it that they were in fact purely visiting these areas and socialising within political circles? They would not want to show their parents what they were actually doing however, Europe seemed to be more accepting of things. It became what was known as a ‘sin bin’; there was an element of the Grand tour that actually was parents acknowledging that their sons needed to ‘let off steam’ abroad so then they were able to come back to Britain and take over the estates. This was an element of the Grand tour that was, again, men developing their masculinity, women never had that level of freedom. Everything women did on the continent was watched and done in such a way that it eliminated any chance of her being questioned for her morality. It was unsaid that men went around drinking and having sex, but it was generally known that they did so. This highlights the masculinity that was being ‘built’ by travelling around Europe. There are many examples of English diplomats having to get involved in affairs regarding British young men in order to get them out of scrapes (In Our Time, 2002). Therefore, although the events were not in the journals because they would not be telling their parents what they were doing, it is generally known that situations like that did happen. “The tour provided a limited period of release before an adulthood in which the young man might be expected to set an example of responsibility and sobriety” (Buzard, 2002, p 41). Europe was the best place to do this because it gave them ability to let off steam with little consequence. Europe was far enough away that many rumours would not reach Britain however at the same close enough to be able to learn how to run the countries because they were similar enough to do so. Therefore, the ideal of masculinity was the mould for these young men to fit into, it was expected of them on return to the UK.

To conclude, the whole idea that young boys went off to become men is a very valid one. The Grand tour was the final bit of training; the consolidation of everything they learned in school. This had its hidden elements however, there were parts that did fit into this idea of being moulded into the masculine man by developing skills in foreign courts and seeking out art and architecture. There was also the element of worry, worries that their reputation would be ruined if their sons wanted to, drink and gamble and other vices. Therefore, it was in their interests to send them away to Europe to do so, however where were the women’s’ choices to do so? So, the main idea of the Grand tour was to build strong masculine men, and this is where the itineraries were probably very similar because there was a set list of what people thought ‘becoming a man was’.

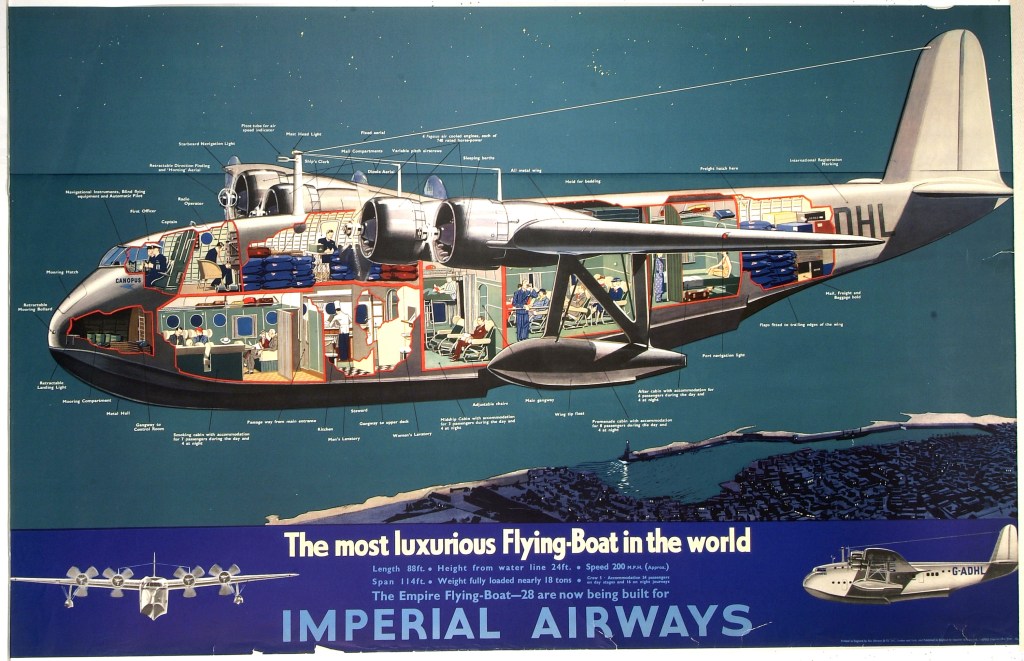

All of the images shown throughout the post are a result of the Grand tour, and show how the tour influenced British taste and style.

Bibliography

Primary sources

- de la Rosa, Gabriella (2015) Collecting the Grand Tour: Treasures of the Ford Collection Available from: https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/features/collecting-the-grand-tour-treasures-of-the-ford-collection(Accessed 17th February 2022)

- Lyttleton (1728-71) News from abroad: Letters Written by British travellers on the Grand Tour

- Sterne, Laurence (1768: 2001) A Sentimental Journey Through France and Italy.

Secondary sources

- BBC In Our Time (2002) The Grand Tour, 13 May. Available from: <http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p00548fs > [Accessed 17th February 2022].

- Black, Jeremy (1985: 2010) The British and the Grand Tour. London: Croom Helm. Social and political reflections

- Buzard, James (2002) ‘The Grand Tour and After (1660-1840)’. In Youngs, Tim (ed.) The Cambridge Companion to travel writing.

- Cohen, Michele (1996) Fashioning Masculinity: national identity and language in the eighteenth century.

- Naddeo, Barbara (2005) ‘Cultural Capitals and cosmopolitanism in eighteenth-century Italy: the historiography on the Grand Tour.’ Journal of Modern Italian Studies

- Sweet, Rosemary (2015) ‘Experiencing the Grand Tour.’ In Cities and the Grand Tour.