Dark tourism has become a popular travel alternative over the years; ranging from 1816 and individuals visiting the battlefield of Waterloo, to the present day where people visit tourist destinations such as the 9/11 memorial in New York and the Dungeon visitor attractions . But this type of travel has faced criticism about its existence and purpose, as dark tourism is associated with the “memorialization of death and suffering” (Oxford languages, 2022). A main question that has arisen alongside the development of dark tourism is that should destinations that are “connected to some of history’s most devastating events be turned into tourist attractions?” (Dark Tourists, 2022). This question can be answered when taking into consideration two aspects. One aspect is if the attraction is treated by tourists as a way to commemorate events of the past and learn about its place in history; and the second aspect can be focused on the matter of the attraction making a profit and being used commercially.

The battlefield of Waterloo:

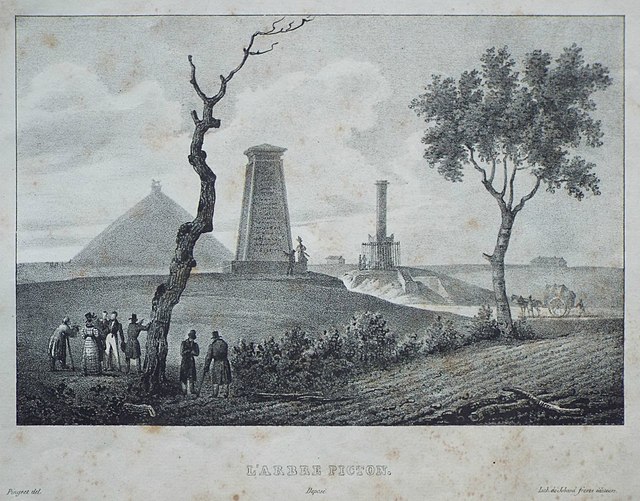

The Battle of Waterloo occurred on the eighteenth of June 1815 and became a popular tourist attraction since its conclusion, as many people travelled to visit the battlefield. In some cases people visited it as the battle was still taking place. The destination itself represents a common form of thanotourism, as it allows tourists to be given the opportunity to see sites where mass or individual deaths have occurred (Seaton, 1999, p.131). Also, Waterloo became the center of a developing tourism industry and it was not unusual in the eighteenth and nineteenth century for places associated with dark tourism to be visited.

Image 1- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:18_June_1815_%E2%80%93_Waterloo_%E2%80%93_L%27Arbre_Picton.jpg#/media/File:18_June_1815_%E2%80%93_Waterloo_%E2%80%93_L’Arbre_Picton.jpg

Image 2- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Waterloo_18th_of_June.JPG#/media/File:Waterloo_18th_of_June.JPG

There are three accounts which can be analysed to show how tourists reacted to the battlefield. They are all first-hand accounts by Scott, Southey and Eaton and detail their experiences as being dark tourists. For instance, in Scott and Southey’s accounts, they both indicate how commercial the location has become, signalling that the attraction was used for making a profit. In addition, Seaton addresses that “local peasants set up stalls and sold relics” (Seaton, 1999, p.137) and Scott recalls in his account that “letters were taken from the pockets of the dead” (Scott, 1816) to be resold. This is reinforced by Southey, who explains that he “bought a French pistol and two ornaments of French infantry for 6 francs” (Southey, 1816:1903). From 1815 and onwards, locals sold items that they discovered and collected from the battle of Waterloo to act as compensation from the disruption that the conflict had caused them. In continuation, this can be related to tourist etiquette. For instance, buying souvenirs is viewed as an action that should be avoided. This is because if an increasing number of people take a memento, it decreases the respect that the attraction receives; which should be left intact and undisturbed (Dark Tourists, 2022). Alternatively, Eaton’s account does not focus on commercial elements but on emotional ones and she writes about how she connected to a location where death had recently occurred. Within this account it is clear that as a tourist, Eaton found her experience traumatic as she did not expect what she saw. For example, she expresses that “no monument points out to future times the spot where they expired” (Eaton, 1817:1888). This shows that she believes those who perished in battle should be commemorated, as it would educate people on the historical event and also allow them to reflect on the sacrifices that were made.

9/11 Memorial:

Speaking of Eaton believing that the battlefield of Waterloo should be treated as a site of commemoration, it can be said that the 9/11 war memorial in New York receives this treatment by the tourists that visit it. 9/11 occurred on the 11th of September 2001 and involved four coordinated terrorist attacks being carried out, causing the death of “2,977 people” (9/11 Memorial & Museum, 2021). The location of the memorial is constructed in the site of the former World Trade Centre, which was destroyed during the attacks. When the decision was made to convert the site into a memorial, the “New York tourist board found it hard to approach its newest attraction” (Pilot guides, 2021). This is because, they did not want to appear “to be capitalising on the tragedy” (Pilot guides, 2021). In terms of dark tourism, it is stated that there is attractiveness about the dark that draws the attention of tourists. In the case of the 9/11 memorial site, it can be classed as an experiential experience, because it permits people to see and witness the location of an event.

For the above slideshow: Images of 9/11 terrorist attack that occurred in 2001 and the memorial Image 1 –https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:National_Park_Service_9-11_Statue_of_Liberty_and_WTC_fire.jpg#/media/File:National_Park_Service_9-11_Statue_of_Liberty_and_WTC_fire.jpg Image 2 – https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/ed/9-11_Memorial_South_Pool.jpg/640px-9-11_Memorial_South_Pool.jpg Image 3- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:9-11_memorial_pool.jpg#/media/File:9-11_memorial_pool.jpg

In addition, the memorial is known to this day of having the purpose to allow individuals to be able to pay their respects to those who lost their lives; but in 2001, after it was determined that the memorial would never be used in a commercial sense, questions did arise about the motive of tourists themselves. For instance, at the time, New York media viewed tourism as a ghoulish act towards social value, which followed a statement announced by the city’s mayor, Giuliani. Giuliani stated that the 9/11 “site was a crime scene, not a tourist attraction” (Dalton, 2014, p.153). A dark aspect of dark tourism is that human beings want to get their head around the complexity of inhumanity; meaning that they want to understand the occurrence of another’s behavior. According to Dalton, a tourists’ motivation for visiting the scene of the attacks in 2001 was fueled more by curiosity than as an act of commemoration; relating to both domestic and international tourists (Dalton, 2014, p.153). Also Dalton continues by stating that tourists’ curiosity was not affiliated with “seeing where people died and taking some sort of morbid pleasure in the act” (Dalton, 2014, p.153), but associates their motivation with being interested in what “the site actually looks like, to make the event real” (Dalton, 2014, p.153). This shows that dark tourism is not always associated with commemoration or the act of making a profit, but includes people just wanting to see a site where a tragic event has happened so that they can experience the aftermath of the event for themselves.

The Dungeon Attractions, UK:

In comparison to the battlefield of Waterloo and the 9/11 memorial in New York; the Dungeons attractions are considered as a form of “lighter dark tourism” (Sharpley and Stone, 2009, p.167), meaning that while it is associated with death and suffering, it has a high tourism infrastructure. In terms of the attraction itself, there are six Dungeon attractions around the UK, ranging from York, London and Edinburgh. Focusing on the London Dungeon, it is described as a thrilling attraction that allows visitors to “see, hear, feel and smell” (The London Dungeon, 2021) gruesome events of the city’s past. When taking into account the act of commemoration and the process of making a profit, it can be said that the Dungeons as a dark tourism attraction, incorporates elements of both. Expressed by Stone and Sharpley “official tourism marketing is progressively exploiting the commercial aspects of tragic history” (Stone and Sharpley, 2009, p.167) and viewed from a money-making perspective, the Dungeons are promoted to tourists in a way that shows them to be fun, and it is indicated that this strategy disguises the attractions dark nature.

In addition, the element of commemoration is still seen to be present in attractions treated as entertainment. According to Ivanova and Light, there are other motives aside from being curious. They state that these include “a desire for learning and understanding” (Ivanova and Light, 2018, p.357) and a “wish to connect with tragic events and a sense of obligation” (Ivanova and Light, 2018, p.357). This being said, it is implied from these statements that commemoration is a main factor as the Dungeon attractions teaches tourists about tragic events of the past through educative processes. This then leads to people remembering what they have learnt, but also remembering the tragic events that individuals had to live through in the past , which in some cases did result in death and suffering; such as the London Plague that is estimated to have killed around 68,596 people between the years 1665 and 1666 (National Archives, 2022).

To contemplate if some of history’s most devastating events should be tourist attractions; by weighing up the evidence collected, it can be concluded that these attractions should exist. This is because by dark tourism being existent, events surrounding the occurrence of death in the past will not be forgotten by future generations; but this does not mean that these sites are always used for the correct purpose. The 9/11 memorial is a location that is focused on commemorating the individuals who lost their lives during the attacks in 2001 and it was made clear that it would exist as a place for people to be respectful. But this shows how dark tourism has developed over the decades, as in 1815, the accounts of Scott and Southey focus upon how the battlefield of Waterloo was appealing to tourists as a chance to gain souvenirs and for local peasants to earn compensation for the disruption that had been caused to their lives. Also in 1815 there were tourists who felt obligated to commemorate the lives of those who had been killed in the conflict and this is revealed through Eaton’s account. Furthermore, it can be said that the Dungeon attractions have more in common with the way that Waterloo was treated compared to the 9/11 memorial as even though the dungeons do make a profit off the many tourists that visit, they are teaching people about events that occurred in history and keeping the memory of them alive. Overall the purpose of dark tourism is associated to how locations are treated by the dark tourists.

Bibliography:

Primary Sources:

Eaton C (1817:1888) Waterloo Days: The narrative of an Englishwoman Resident at Brussels in June, 1815. London: George Bells & Sons

Dalton D (2014) Dark Tourism and Crime. Taylor and Francis: Oxfordshire. Pp.1-230

Ivanova P, Light D (2018) ‘“It’s not that we like death or anything”: Exploring the motivations and experiences of visitors to a ‘lighter’ darker tourism attraction.’ Journal of Heritage Tourism. Volume 13, Issue 4. Pp.356-369

Scott J (1816) Paris Revisited in 1815, By way of Brussels, Including a walk over the Field of Battle at Waterloo. Boston: Wells & Lilly

Seaton A.V (1999) ‘War and thanotourism: Waterloo 1815-1914.’ Annals of Tourism Research. Volume 16, Issue 1. Pp. 130-158

Southey R (1816:1903) A journal of a Tour of the Netherlands in the Autumn of 1815. London: Heinemann

(Eds) Stone P.R, Sharpley R (2009) The Darker Side of Travel: The Theory and Practice of Dark Tourism. Channel View Publication. Pp.1-275

Secondary Sources:

Dark Tourists (2022) ‘Welcome to Dark Tourists.’ Available <https://darktourists.com/home/> Accessed: 21st February 2022

9/11 Memorial and Museum (2021) ‘What happened on 9/11?’ Available <https://www.911memorial.org/911-faqs> Accessed: 23rd February 2022

Oxford Languages (2022) ‘Dark Tourism definition.’ Available <https://oxfordlanguages.oup.com/google-dictionary-en/> Accessed: 21st February 2022

Pilot guides (2021) ‘Ground Zero & the phenomena of Dark Tourism.’ Available <https://pilotguides.com/articles/ground-zero-the-phenomena-of-dark-tourism/> Accessed: 23rd February 2022

The National Archives (2022) ‘Great Plague of 1665-1666.’ Available <https://wwwnationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/great-plague/> Accessed: 24th February 2022

The London Dungeon (2021) ‘What is the Dungeon?’ Available <https://www.thedungeons.com/london/whats-inside/what-is-the-dungeon/> Accessed: 24th February 2022