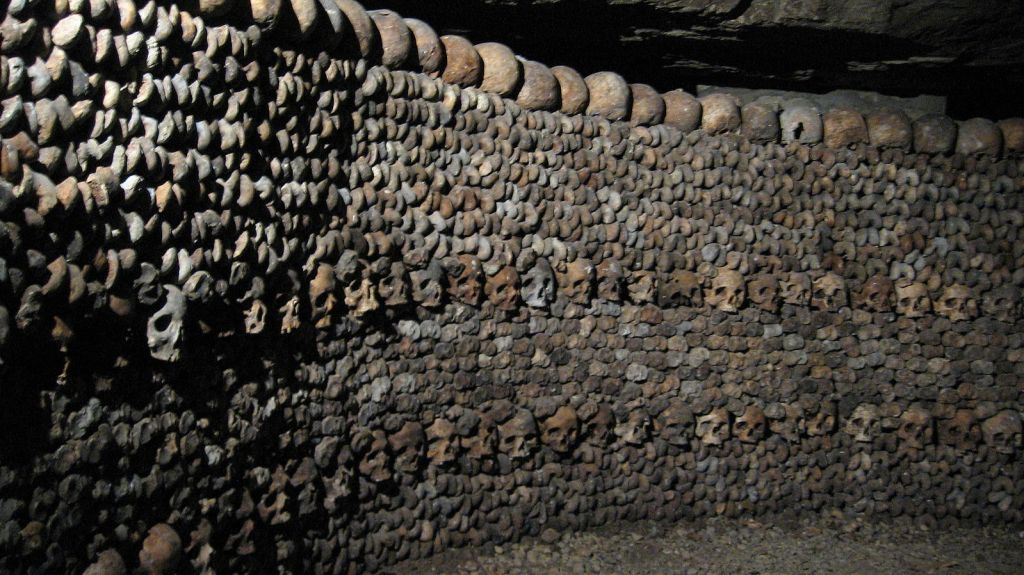

Over the past 500 years, travelling has become synonymous with experiencing a multitude of cultures, exploring, relaxing, and entertainment. From this, the development of sex tourism has emerged. Historically linked with the growing ideas of sexual liberation and pleasure, sex tourism has evolved to not only experience these things but also consuming the heritage and cultural significance surrounding it.

From the Grand Tour in the 16th century to more recent times with the emergence of package holidays, changing societal norms links between travel and sexual freedom are incredibly apparent. Demonstrating a shift in indulgence to heritage around sex, encouraging consumers to dig deeper into the complexities that museums navigate- the fine line between entertaining while conveying important information and meeting the new modern-day audience needs. This blog post will explore these complexities surrounding the rise in sex tourism and its close links with heritage. Whilst also looking at the links between past and present tourism and how this has played a role in how museums navigate the tricky task of being informative vs educational.

This blog will focus on Amsterdams Sex Museum , known for its imagined geographies, such as picturesque landscapes, but also for its liberal ideas around sex, making it a hot spot with the 18-30 demographic who want the chance to experience the rich culture and liberation, like those who undertook the Grand Tour. Another example is the New York Museum of Sex

Origins of sex tourism and heritage

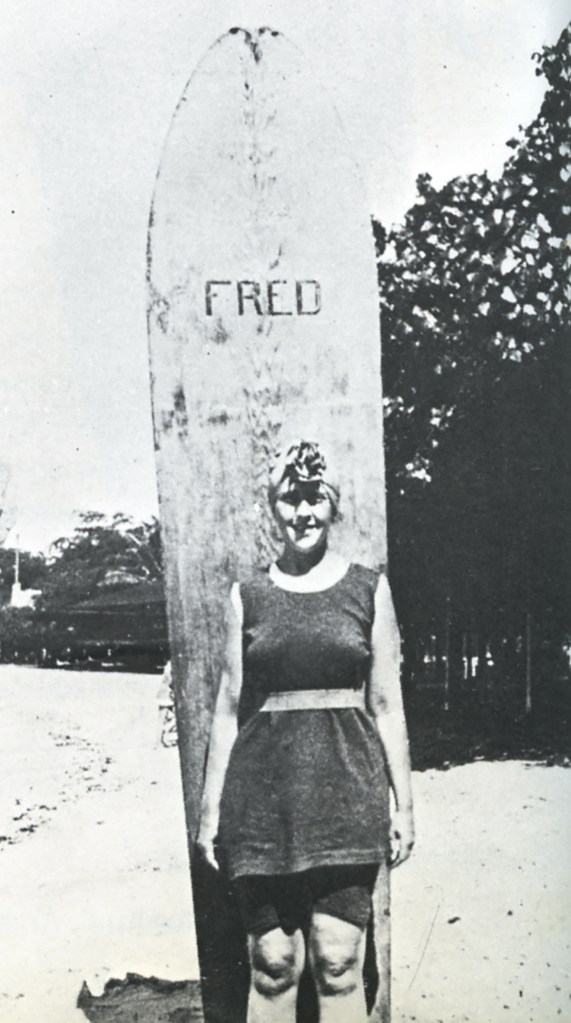

The phrase Grand Tour was first coined in The Voyage of Italy by Richard Lasses in 1670; what we now know as the grand tour occurred as far back as the 16th century. Although no set route, stops included France, Italy and Greece. Traditionally, it started as something only undertaken by noble men looking to finish their education; however, in the 1800s, women soon started to experience the cultural richness the Grand Tour had to offer. For many, they were solely independent away from traditional norms, so because of this, the trips often tended to be part education and part ‘continental booze-up, a prolonged itinerary of excessive consumption, gambling and sexual experimentation’ (Nast, 2022). Ingles states that the Grand Tour offered a ‘search for new selves down forbidden paths in paradise gardens, a giving of oneself to strangers and to suddenly discovered friendships, a stripping-off of old attire, both literal and metaphoric’ (Inglis, 2005, p.136).

Although accounts were written both within the Grand Tour and even in Victorian times, often scared of repercussions of breaking the social norms of the day, many require a modern audience to read between the lines. A prime example is Margaret Fountaine’s love among butterflies. A published diary of Victorian lady’s travels. She details her falling in love with her guide/translator, Khalil Neimy, in Syria. She wrote that she ‘claimed all the privileges of an accepted lover, though I did not give him all he asked.’ (Fountaine, 1980, p.125). Diaries like this had to be published retrospectively; when the diaries were given to the castle museum in 1940 following her death, there was a letter asking for them not to be put on display in 1978 showing that even in death Fountaine feared the backlash.

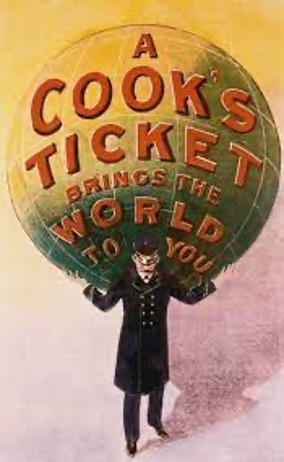

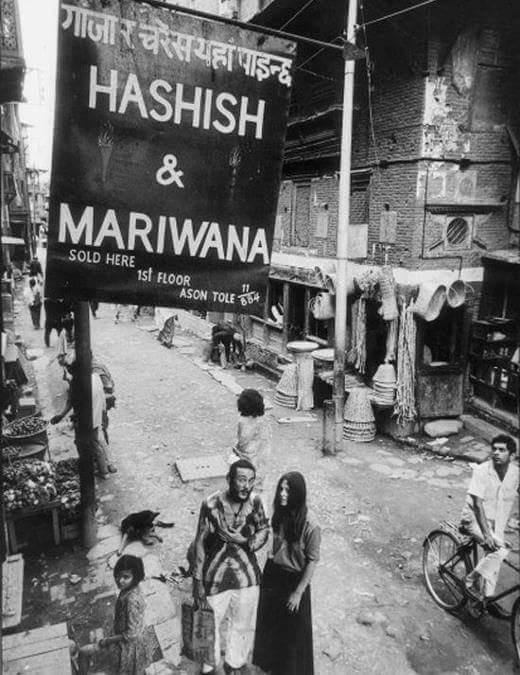

The creation of package holidays in 1841 by Thomas Cook also helped create a revolution. The world wars brought stagnation to the tourist industry; however, the idea of escaping from the constraints of war-torn Britain appealed to many, and in 1947, holidays continued back up. The growth in travel and economy with a new increase in disposable income coupled with the introduction of new ideas such with the introduction of contraception and an increasing urge for self-discovery. The 1970s saw the birth of the stereotypical 18-30s holiday such as Club 18-30 having the ‘catchphrase “sun, sex and sea” Club 18–30 became a go-to tour operator for people travelling without their parents for the first time.’ (Dickinson, 2018). Seemingly sharing several comparisons with the Grand Tour: away from social norms, pushing the limits, offer a sense of escapism and enjoying the sexual freedom.

Education vs Entertainment

One way in which museums balance entertainment and education is using technology. For example, the celestial bodies VR exhibition in 2017. A fully immersive experience where the audience were encouraged to use all senses as they were transported by VR into a different dimension. Based on the song set it off by Diplos, the VR experience allowed the audience to explore a fantasy sci-fi hallucinogenic land with exotic dancers. The use of technology such as VR in museums shows the capabilities of modern technology within museum settings drawing a modern crowd in. Other technology uses include the virtual tour run by the sex museum in Amsterdam. This is key to bringing in a new audience and allowing them to experience the various artefacts that the museum offers that they wouldn’t otherwise get to experience.

Another technique used is the type of language. Amsterdam Sex Museum describes itself as ‘educational & funny’ (The Sex Museum, n.d). This can be seen in many novelty items amongst important artefacts, informative facts, and information. Using this language is paramount in keeping the audience engaged and entertained, which in turn will help promote education within the museums. Although sex museums are often thought-provoking, the tone and language used allows for the information to be more digestible. Another thing they have done is make sure that they appeal to a wide range of exhibitions that cater to different audiences and that they are represented, such as the whole exhibition on LGBTQ+. The exhibition hones in on the growth in pride parade, the development of gay rights worldwide and the drag queen industry.

However, in contrast, the museum stays informative by running workshops and lectures. An example of this would be within the New York Museum of Sex running workshops on topics such as reproductive health to help destigmatise it. For example, in 2020 they ran the Laia Abril–On Abortion: And the Repercussions of Lack of Access . At a time when women’s reproductive health is a heated topic within America the exhibition highlights the importance of women’s health care and the taboo around it. In the centre of the exhibition were chairs with a TV Infront showing a clip of Todd Akin, who made remarks live on TV in 2012 that even in rape cases, abortion isn’t acceptable, and women have control over what happens. The chairs in front of the TV metaphorically and physically actively encourage discussion. Similarly, Amsterdam has also ensured to be inclusive, such as objects from various cultures, such as China and Greece. It also includes pop culture references such as Marilyn Monroe, the most recognised sex symbol and uses a broad range of exhibitions on various things, such as the BDSM exhibition.

Controversies

Although this has not come without its challenges, the Amsterdam city council announced the discouragement of both stag and hen parties, with the deputy mayor saying that it was done to ‘keep out visitors that we do not want’ (Doyle, 2022). Showing the impact that imagined geographies have had on tourist destinations, especially the ones with more sexual connotations. This would also have impacts on places such as the sex museum being a prime place that they would often visit. Additionally, there has been reports of sexual harassment to staff working within the museums. Staff members at the Museum of sex reported to have experienced ‘constant and persistent sexual harassment’ from customers, adding that these complaints were not dealt with by management and were simply allowed to happen (Burke, 2019). The case was ultimately closed with a settlement (unreported how much), it raises the question about how much protection the staff have and goes against everything a sex museum should be- safe and welcoming for both staff and customers.

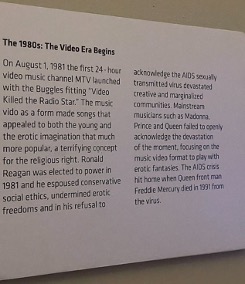

Recently, the Museum of sex has also been in hot water for misinformation. The museum misreported that Madonna had failed to help support the AIDS crisis at an exhibition of the 1980s music videos. Claiming that ‘mainstream museums such as Madonna….failed to openly acknowledge the devastation of the movement’ (Museum of Sex, 2024). The museum faced significant backlash and released a public apology ‘we have since amended our museum signage to point out Madonna’s early steps to bring attention to the aid crisis. We regret any negative light this many have shined. It was purely unintentional’ (Museum of Sex, 2024). Undeniably these types of museums have and do face constant religious backlash from the likes of the catholic league, who claimed the Museum of Sex to be ‘a death chamber that would acknowledge all the wretched diseases promiscuity has caused’ (Chancellor, 2002).

Conclusion

To conclude, there has been a very apparent change in the need to explore sexuality over the past 500 years with tourism. Going from the need to experience sexual liberation to the more modern world wanting to experience this but to also wanting to explore the heritage that has grown because of this. The growing interest in sexual heritage, museums have had to adapt to the growth and rise in sex museums. However, there is a very fine line between education and information, and sex museums appear to dance along this very line- although some not always seeming to get it right.

Bibliography

Burke, M. (2019). Ex-Museum of Sex tour guide sues over alleged sexual harassment. [online] NBC News. Available at: https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/ex-museum-sex-tour-guide-sues-over-alleged-sexual-harassment-n1019631 [Accessed 29 Feb. 2024].

Chancellor, A. (2002). The opposite of sex. The Guardian. [online] 28 Sep. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2002/sep/28/usa.comment [Accessed 2 Mar. 2024].

Dickinson, G. (2018). Outdated and irrelevant – the demise of Club 18-30 comes as no surprise. [online] The Telegraph. Available at: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/travel/comment/club-18-30-holidays-demise/.

Doyle, E. (2022). Amsterdam campaign tells ‘nuisance’ British tourists to ‘stay away’ from capital. [online] The Independent. Available at: https://www.independent.co.uk/travel/news-and-advice/amsterdam-campaign-nuisance-british-tourists-stay-away-b2240003.html.

Fountaine, M. (1980). Love Among the Butterflies. HarperCollins.

Inglis, F. (2005). The Delicious History of the Holiday. Routledge.

Laia Abril. (2020). On Abortion, The Museum of Sex, New York, 2020. [online] Available at: https://www.laiaabril.com/exhibition/on-abortion-museum-of-sex/.

Lassels, R. (1670). The Voyage Of Italy, Or A Compleat Journey Through Italy.

Museum of Sex. (n.d.). About. [online] Available at: https://www.museumofsex.com/about [Accessed 2 Mar. 2024].

Museum of Sex. (2020). Laia Abril: On Abortion. [online] Available at: https://www.museumofsex.com/exhibitions/laia-abril-on-abortion/#:~:text=In%20her%20first%20chapter%2C%20On [Accessed 2 Mar. 2024].

Nast, C. (2022). How the Grand Tour transformed eighteenth-century culture in Britain. [online] House & Garden. Available at: https://www.houseandgarden.co.uk/gallery/the-grand-tour.

Sex Museum Amsterdam (n.d.). Sexmuseum Amsterdam – Ontdek de Venustempel van Amsterdam. [online] Available at: https://sexmuseumamsterdam.nl.

Stanley, I. (2024). Museum of Sex apologizes to Madonna for claims she ignored AIDS crisis. [online] Mail Online. Available at: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-12948533/museum-sex-nyc-madonna-apology-aids-crisis.html#:~:text=New%20York%20City%27s%20Museum [Accessed 2 Mar. 2024].

The Guardian (2018). Thomas Cook: the father of modern tourism – archive, 22 November 1958. The Guardian. [online] 22 Nov. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/travel/2018/nov/22/thomas-cook-the-father-of-modern-tourism-archive-1958.

Zoffany, J. (n.d.). Tribuna of the Uffizi. [Painting] History Hit. Available at: https://www.historyhit.com/what-was-the-grand-tour/ [Accessed 2 Mar. 2024].

![Sykes, H. (1980s) Photograph taken in Majorca, Spain [Online image] Available from: https://www.alamy.com/1980s-tourism-spain-magaluf-majorca-english-owned-bars-restaurants-image4114638.html](https://britons-abroad.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/majorca-2.jpg?w=640)